U.S. Constitution

See other U.S. Constitution Articles

Title: You have NO IDEA what’s coming: Virginia Dems to unleash martial law attack on 2A counties using roadblocks to confiscate firearms and spark a shooting war

Source:

Government Slaves/Natural News

URL Source: https://governmentslaves.news/2019/ ... arms-and-spark-a-shooting-war/

Published: Dec 19, 2019

Author: Mike Adams

Post Date: 2019-12-21 11:10:14 by Deckard

Keywords: None

Views: 43976

Comments: 171

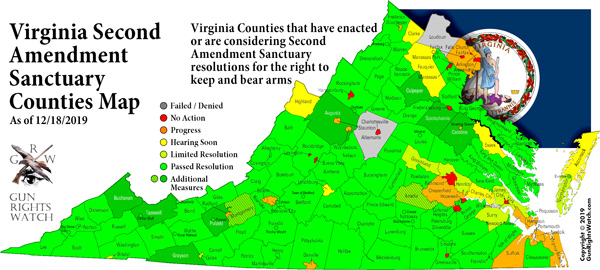

After passing extremely restrictive anti-gun legislation in early 2020, Virginia has a plan to deploy roadblocks at both the county and state levels to confiscate firearms from law-abiding citizens (at gunpoint, of course) as part of a deliberate effort to spark a shooting war with citizens, sources are now telling Natural News. Some might choose to dismiss such claims as speculation, but these sources now say that Virginia has been chosen as the deliberate flashpoint to ignite the civil war that’s being engineered by globalists. Their end game is to unleash a sufficient amount of violence to call for UN occupation of America and the overthrow of President Trump and the republic. Such action will, of course, also result in the attempted nationwide confiscation of all firearms from private citizens, since all gun owners will be labeled “domestic terrorists” if they resist. Such language is already being used by Democrat legislators in the state of Virginia. The Democrat-run impeachment of President Trump is a necessary component for this plan, since the scheme requires Trump supporters to be painted as “enraged domestic terrorists” who are seeking revenge for the impeachment. This is how the media will spin the stories when armed Virginians stand their ground and refuse to have their legal firearms confiscated by police state goons running Fourth Amendment violating roadblocks on Virginia roads. Roadblocks will be set up in two types of locations, sources tell Natural News: 1) On roads entering the state of Virginia from neighboring states that have very high gun ownership, such as Kentucky, Tennessee and North Carolina, and 2) Main roads (highways and interstates) that enter the pro-2A counties which have declared themselves to be Second Amendment sanctuaries. With over 90 counties now recognizing some sort of pro-2A sanctuary status, virtually the entire State of Virginia will be considered “enemy territory” by the tyrants in Richmond who are trying to pull off this insidious scheme. As the map shows below, every green county has passed a pro-2A resolution of one kind or another. As you can see, nearly the entire state is pro-2A, completely surrounding the Democrat tyrants who run the capitol of Richmond. The purpose of the roadblocks, to repeat, has nothing to do with public safety or enforcing any law. It’s all being set up to spark a violent uprising against the Virginia Democrats and whatever law enforcement goons are willing to go along with their unconstitutional demands to violate the fundamental civil rights of Virginian citizens. Over 90 Virginian counties, cities and municipalities have so far declared themselves to be pro-2A regions, meaning they will not comply with the gun confiscation tyranny of Gov. Northam and his Democrat lackeys. Democrats in Virginia have threatened to activate the National Guard to attack pro-2A “terrorists,” and a recent statement from the Guard unit in Virginia confirms that the Guard has no intention to resist Gov. Northam’s outrageous orders, even if they are illegal or unconstitutional. One county in Virginia — Tazewell — has already activated its own militia in response. As reported by FirearmsNews.com: In addition to passing their Second Amendment Sanctuary Resolution, the county also passed a Militia Resolution. This resolution formalizes the creation, and maintenance of a defacto civilian militia in the county of Tazewell. And to get a better understanding why the council members passed this resolution, Firearms News reached out to one of its members, Thomas Lester. Mr. Lester is a member of the council, as well as a professor of American History and Political Science. Firearms News: Councilman Lester, what are the reasons behind passing this new resolution, and what does it mean for the people of Tazewell County? Tom Lester: … the purpose of the militia is not just to protect the county from domestic danger, but also protect the county from any sort of tyrannical actions from the Federal government. Our constitution is designed to allow them to use an armed militia as needed. If the (Federal) government takes those arms away, it prevents the county from fulfilling their constitutional duties. The situation is escalating rapidly in Virginia, which is precisely what Democrats and globalists are seeking. As All News Pipeline reports: With many Virginia citizens angry with the threat of tyranny exploding there, ANP was recently forwarded an email written by a very concerned Virginia citizen who warned that Democratic leadership is pushing Virginia there towards another ‘shot heard around the world’ with Virginia absolutely the satanic globalists new testing ground for disarming all of America in a similar fashion should they be successful there. And while we’ll continue to pray for peace in America, it’s long been argued that it’s better to go down fighting than to be a slave to tyranny for the rest of one’s life. And with gun registration seemingly always preceding disarmament and disarmament historically leading to genocide, everybody’s eyes should be on what’s happening now in Virginia. With the mainstream media clearly the enemy of the American people and now President Trump confirming they are ‘partners in crime’ with the ‘deep state’ that has been attempting an illegal coup upon President Trump ever since he got into office, how can outlets such as CNN, MSNBC, the NY Times, Washington Post and all of the others continuously pushing the globalists satanic propaganda be held accountable and responsible for the outright madness they are unleashing upon America? Where is all this really headed? The bottom line goal of the enemies of America is to transform the country into a UN-occupied war zone, where UN troops go door to door, confiscating weapons from the American people. President Trump will be declared an “illegitimate dictator” and accused of war crimes, since Democrats and the media have already proven they can dream up any crime imaginable and accuse the President of that crime, without any basis in fact. And as we know with the Dems, if they can’t rule America, they will seek to destroy it. Causing total chaos is their next best option to resisting Trump’s efforts to drain the swamp, since the Dems know they can’t defeat Trump in an honest election. Expect Virginia to be the ignition point for all this. Even the undercover cops who work there are now warning about what’s coming. Via WesternJournal.com: Virginia’s Democratic politicians appear to be ready to drive the state into a period of massive civil unrest with no regard for citizens’ wishes, but conservatives in the commonwealth will not be stripped of their rights without a fight. In the face of expected wide-reaching bans on so-called assault weapons, high-capacity magazines, and other arms protected under the 2nd Amendment, Virginians are standing up to Democratic tyranny. A major in the Marine Corps reserves took an opportunity during a Dec. 3 meeting to warn the Board of Supervisors of Fairfax County about trouble on the horizon. Ben Joseph Woods spoke about his time in the military, his federal law enforcement career and his fears about where politicians are taking Virginia. “I work plainclothes law enforcement,” Woods said. “I walk around without a uniform, people don’t see my badge, people don’t see my gun, and I can tell you: People are angry.” Woods said that the situation in Virginia is becoming so dangerous that he is close to moving his own wife and unborn child out of the state. The reason is because my fellow law enforcement officers I’ve heard on more than one occasion tell me they would not enforce these bills regardless of whether they believe in them ideologically,” Woods said, “because they believe that there are so many people angry — in gun shops, gun shows, at bars we’ve heard it now — people talking about tarring and feathering politicians in a less-than-joking manner.” As Woods mentioned politicians themselves could very well be in danger because of their decisions, several rebel yells broke out as the crowd cheered him on. Stay informed. Things are about to happen over the next 10 months that you would have never imagined just five years ago. And to all those who mocked our warnings about the coming civil war, you are about to find yourself in one. Sure hope you know how to run an AR platform and build a water filter. Things won’t go well for the unprepared, especially in the cities. And, by the way, Richmond is surrounded by patriots. At what point will the citizens of Virginia decide to arrest and incarcerate all the lawless, treasonous tyrants in Richmond who tried to pull this stunt? I have a feeling there’s about to be a real shortage of rope across Virginia…

The gun confiscation roadblocks are almost sure to start a shooting war

The enemies of America want to turn the entire country into a UN-occupied war zone and declare President Trump to be an “illegitimate dictator”

Post Comment Private Reply Ignore Thread

Top • Page Up • Full Thread • Page Down • Bottom/Latest

#1. To: Deckard (#0)

Really?

The UN? Vegetarians eat vegetables. Beware of humanitarians!

https://pluralist.com/tazewell-militia-resolution/ By Pluralist | Dec 16, 2019 One southwestern Virginia county is fiercely pushing back against proposed restrictions on gun rights in the state. Earlier this month, the Tazewell County Board of Supervisors passed two resolutions aimed at opposing potential restrictions on gun possession and ownership. One made Tazewell County a “Second Amendment sanctuary.” The other authorized funding for the formation of a well-regulated militia, WJHL reported. Both resolutions were unanimously passed on Dec. 3 to loud cheers from a standing room-only crowd at the Board of Supervisors meeting, according to the Bristol Herald Courier. “Our position is that Article I, Section 13, of the Constitution of Virginia reserves the right to ‘order’ militia to the localities,” County Administrator Eric Young, who helped draft the ordinances, told the Herald Courier. “Therefore, counties, not the state, determine what types of arms may be carried in their territory and by whom. So, we are ‘ordering’ the militia by making sure everyone can own a weapon.” Southern District Supervisor Mike Hymes said people in Tazewell County “feel the need to have a gun to protect themselves and their property.” “We live in an area where the nearest deputy might be 45 minutes away,” Hymes told the Herald Courier. Tazewell County Sheriff Brian Hieatt told NBC affiliate WWVA the militia resolution “gives us some teeth to be able to act and do something if a law comes out dealing with firearms that we see is illegal.” According to Tazewell County Board of Supervisors Chairman Travis Hackman, the ordinance is aimed at sending a message to the state’s legislators in Richmond. Virginia Democrats, who in November seized control of both houses of the state’s legislature for the first time in more than two decades, made gun control laws a focus of their campaigns. Democrats’ electoral triumph has sparked fears of increased restrictions on firearms possession, which the state’s pro-gun advocates say infringe on their Second Amendment rights. Last week, Democrats announced they were amending a pending ban on “assault weapons” in the face of political pressure. An early draft of the bill would have made it a felony to possess any firearm defined as an “assault weapon.” Gun rights groups were particularly concerned by the lack of an exception for those who already possess such weapons. The ban is backed by Democratic Gov. Ralph Northam, whose spokeswoman, Alena Yarmosky, told the Virginia Mercury that “the governor’s assault weapons ban will include a grandfather clause for individuals who already own assault weapons, with the requirement they register their weapons before the end of a designated grace period.” The move to confiscate guns faced immense grassroots opposition in the state, which has seen a majority of its counties declare themselves “Second Amendment sanctuaries.” A portion of the funds allocated by the militia resolution will go to programs such as the Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts, and weapons training courses, according to WJHL. Cover image: New Virginia Militia. (Facebook) - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - It is clear that the Tazewell County Board of Supervisors has passed not just one, but two resolutions, and they have sent a message. Yes, civil war is coming and they are prepared, with a militia having been formed, see picture above. When the 82nd Airborne arrives, as surely it will, the Tazewell Board of Supervisors will issue a third resolution, informing the 82nd Airborne that the militia has them surrounded, that there is no escape, and demand their surrender. The 82nd Airborne will surely surrender, knowing as they must, that one does not fuck with a superhero, and the Tazewell Militia has not one, but ten superheroes. The Fantastic Four were fabulous but the Tazewell Ten are terrifying. Following the surrender of the U.S. Armed Forces, the Tazewell County Board of Supervisors will issue a fourth resolution, establishing the sovereign nation of Tazewell.

Jim Talbert TAZEWELL, Va. — Tazewell County joined the ranks of “Second Amendment Sanctuary” counties on Tuesday — and took it one step further. Before a crowd of more than 200, the Board of Supervisors unanimously passed two resolutions during their meeting on Tuesday night. The Second Amendment Sanctuary resolution and a resolution promoting the order of militia within Tazewell County both passed to loud cheers from a crowd that overflowed the 189-seat board room. Board Chairman Travis Hackworth announced at the beginning of the meeting that both resolutions would be unanimously passed. The militia resolution was approved on a poll earlier this month, but county residents via Facebook and other means kept asking for the sanctuary resolution as well. Hackworth said board members started getting messages from state legislators following the Nov. 5 election, which saw Democrats take control of both the House of Delegates and the state Senate for the first time in 25 years. He said elected officials expressed concern that legislation might pass that would chip away at Second Amendment rights. Southern District Supervisor Mike Hymes contacted Interim County Attorney Chase Collins and had him get a copy of the sanctuary county legislation passed in Carroll County, one of the first counties in the state to pass a resolution protecting gun rights, and similar resolutions from other localities. “We went through them with three attorneys. It was not our intent to water anything down. We wanted something with teeth in it. Something we could use to file injunctions and defend in court,” Hackworth said. County Administrator Eric Young, one of the attorneys, along with Collins and Eric Whitesell, who helped draft the ordinances, said the resolutions allow the county to take action in the event that state or federal laws are passed violating the Second Amendment. Board member Charlie Stacy, also an attorney, praised the citizens for their knowledge of upcoming bills in the state Legislature. “This board is blessed with three lawyers, and they designed a strategy to win in a court of law,” Stacy said. He said the ordinances approved by the board allow the county to challenge any resolution in state or federal court. “The resolution is truly designed to allow us to hire lawyers to see that laws infringing on the Second Amendment never last any longer than it takes a court to remove them,” he said. Both resolutions call for the elimination of funding to any enforcement of laws that infringe upon the rights of law-abiding citizens to keep and bear arms. Stacy and other board members said a concern that state leaders might cut off funding to the county or remove elected officials who refuse to enforce state law prompted them to pass the militia ordinance. “Our position is that Article I, Section 13, of the Constitution of Virginia reserves the right to ‘order’ militia to the localities,” Young said. “Therefore, counties, not the state, determine what types of arms may be carried in their territory and by whom. So, we are ‘ordering’ the militia by making sure everyone can own a weapon.” The sanctuary resolution cites the Second Amendment to the Constitution, which states “the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed.” Hymes said he knew what his constituents wanted and asked for the amendment last month. “We live in an area where the nearest deputy might be 45 minutes away. People feel the need to have a gun to protect themselves and their property,” he said. In addition to allowing the county to order a militia, the ordinance calls for concealed weapons training for all residents of the county who are eligible to own a gun and the teaching of firearms safety in public schools. Sheriff Brian Hieatt and newly elected Commonwealth’s Attorney Chris Plaster both expressed their support for the resolutions and belief that the Constitution of the United States supersedes state laws.

Jade Burks TAZEWELL COUNTY (WVVA) -- More than 30 counties across the Commonwealth have passed 'Second Amendment Sanctuary' resolutions -- including Tazewell County. But what does that really mean? "What the Second Amendment sanctuary resolution is designed to do, primarily, is to demonstrate to the Virginia General Assembly the vast amount of people in the Commonwealth of Virginia that are fundamentally opposed to the proposed regulations that are there being submitted for the 2020 General Assembly that are significantly restricted on the Second Amendment rights to possess or operate firearms," says Eastern District Representative of the Tazewell County Board of Supervisors, Charles Stacy. But what protection does that provide to the residents of "sanctuary counties?" Officials say the resolutions are more like a 'symbol of opposition.' "It's almost more of a proclamation of what the boards are prepared to do," Stacy says. "It's a strong message to our legislators let them know that we don't want to see any changes in our gun laws," says Tazewell County Sheriff Brian Hieatt. "So we're seeing county after county doing the same thing and passing similar resolutions, to say that we do not want to infringe on our rights to have our weapons." Therefore, the resolutions don't provide a legal defense. "You can't simply present this in a court and say, 'Your Honor, I'm not guilty of possessing a firearm that the General Assembly has deemed illegal, because my home county passed a second amendment sanctuary resolution,'" Stacy explained. "What the resolutions are designed to do is prevent that legislation from even coming out of the Virginia General Assembly, by giving the proclamation of the localities to the General Assembly before they vote." But a second resolution is providing the residents of Tazewell County with more protection. "Tazewell County also passed a militia resolution, which gives us some teeth to be able to act and do something if a law comes out dealing with firearms that we see is illegal," Sheriff Hieatt explained. That resolution actually gives Tazewell County the opportunity to challenge any law it feels violates the Second Amendment rights of its citizens. "The stronger legal arguments are the ones that we are preparing in the second resolution to allow us a constitutional challenge," Stacy said. "If the Virginia General Assembly passes these laws as they are written, and the governor signs them; we have the immediate ability to challenge those in both the Virginia and the United States Courts to challenge the constitutionality of those laws." If the laws do pass, Tazewell County is willing to do just that. "Right now we're all just hoping that the public outpouring all across the Commonwealth is enough to maybe inform the General Assembly that on these particular issues, their proposed legislation has gone too far," Stacy said. "And if the people deem it to be a violation of their constitutional rights, they're not going to just sit back and take that. They're going to advocate, they're going to fight that as hard as they can. So hopefully that'll be heard in Richmond, and the General Assembly will modify what's been proposed to make it a little bit more constitutional, but also a little bit more along the wishes of what the people of the Commonwealth really want."

Outright banning and confiscation of weapons legally owned by American citizens is tyranny. There's nothing illegal about standing up to tyrants - with force if necessary. You gun-grabbing assholes need to understand that.

Government is in the last resort the employment of armed men, of policemen, gendarmes, soldiers, prison guards, and hangmen. Remember that picture of a blue helment full of holes?

If they are going to set up roadblocks on roads coming INTO the State, that is a huge tactical error if they are wanting peace. If something breaks out AT the borders, the people within the State will be left to their own devices while LE does what it does best, send everyone to the one trouble spot.

THIS IS A TAG LINE...Exercising rights is only radical to two people, Tyrants and Slaves. Which are YOU? Our ignorance has driven us into slavery and we do not recognize it.

You cannot vote away a Right to keep and bear arms. ANY law restricting the Right is unconstitutional and SHOULD BE MET with any force the citizens protecting their rights choose. Death to Tyrants, not jail.

THIS IS A TAG LINE...Exercising rights is only radical to two people, Tyrants and Slaves. Which are YOU? Our ignorance has driven us into slavery and we do not recognize it.

True, as long as you understand what the Right to Keep and Bear Arms (RKBA) consists of. The 2nd Amendment says "the right ... shall not be infringed." What that connotes depends on what "the right" was defined as; what is it that cannot be infringed. The U.S. Supreme Court has not accepted the edicts of wacko dingbats on the internet that includes the right to keep any weapon, or that there can be no regulations or restrictions. The "right to keep and bear arms" existed in the colonies, was brought forth into the states before the union, and was protected by the 2nd Amendment from Federal infringement. The right which existed in the colonies came from the English common law. The Framers saw no need to explain to themselves what that right to keep and bear arms was. It had been in the colonies since before they were born. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/blackstone_bk1ch1.asp Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England Book the First - Chapter the First: Of the Absolute Rights of Individuals (1765) It has never meant a right to carry any and all weapons for any purpose. It does not mean that today. http://laws.findlaw.com/us/000/07-290.html Certiorari to The United States Court Of Appeals for the District Of Columbia Circuit No. 07-290.Argued March 18, 2008--Decided June 26, 2008 District of Columbia law bans handgun possession by making it a crime to carry an unregistered firearm and prohibiting the registration of handguns; provides separately that no person may carry an unlicensed handgun, but authorizes the police chief to issue 1-year licenses; and requires residents to keep lawfully owned firearms unloaded and dissembled or bound by a trigger lock or similar device. Respondent Heller, a D. C. special policeman, applied to register a handgun he wished to keep at home, but the District refused. He filed this suit seeking, on Second Amendment grounds, to enjoin the city from enforcing the bar on handgun registration, the licensing requirement insofar as it prohibits carrying an unlicensed firearm in the home, and the trigger-lock requirement insofar as it prohibits the use of functional firearms in the home. The District Court dismissed the suit, but the D. C. Circuit reversed, holding that the Second Amendment protects an individual's right to possess firearms and that the city's total ban on handguns, as well as its requirement that firearms in the home be kept nonfunctional even when necessary for self-defense, violated that right. Held: 1. The Second Amendment protects an individual right to possess a firearm unconnected with service in a militia, and to use that arm for traditionally lawful purposes, such as self-defense within the home. Pp. 2-53. (a) The Amendment's prefatory clause announces a purpose, but does not limit or expand the scope of the second part, the operative clause. The operative clause's text and history demonstrate that it connotes an individual right to keep and bear arms. Pp. 2-22. (b) The prefatory clause comports with the Court's interpretation of the operative clause. The "militia" comprised all males physically capable of acting in concert for the common defense. The Antifederalists feared that the Federal Government would disarm the people in order to disable this citizens' militia, enabling a politicized standing army or a select militia to rule. The response was to deny Congress power to abridge the ancient right of individuals to keep and bear arms, so that the ideal of a citizens' militia would be preserved. Pp. 22-28. (c) The Court's interpretation is confirmed by analogous arms-bearing rights in state constitutions that preceded and immediately followed the Second Amendment. Pp. 28-30. (d) The Second Amendment's drafting history, while of dubious interpretive worth, reveals three state Second Amendment proposals that unequivocally referred to an individual right to bear arms. Pp. 30-32. (e) Interpretation of the Second Amendment by scholars, courts and legislators, from immediately after its ratification through the late 19th century also supports the Court's conclusion. Pp. 32-47. (f) None of the Court's precedents forecloses the Court's interpretation. Neither United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U. S. 542, 553, nor Presser v. Illinois, 116 U. S. 252, 264-265, refutes the individual-rights interpretation. United States v. Miller, 307 U. S. 174, does not limit the right to keep and bear arms to militia purposes, but rather limits the type of weapon to which the right applies to those used by the militia, i.e., those in common use for lawful purposes. Pp. 47-54. 2. Like most rights, the Second Amendment right is not unlimited. It is not a right to keep and carry any weapon whatsoever in any manner whatsoever and for whatever purpose: For example, concealed weapons prohibitions have been upheld under the Amendment or state analogues. The Court's opinion should not be taken to cast doubt on longstanding prohibitions on the possession of firearms by felons and the mentally ill, or laws forbidding the carrying of firearms in sensitive places such as schools and government buildings, or laws imposing conditions and qualifications on the commercial sale of arms. Miller's holding that the sorts of weapons protected are those "in common use at the time" finds support in the historical tradition of prohibiting the carrying of dangerous and unusual weapons. Pp. 54-56. 3. The handgun ban and the trigger-lock requirement (as applied to self-defense) violate the Second Amendment. The District's total ban on handgun possession in the home amounts to a prohibition on an entire class of "arms" that Americans overwhelmingly choose for the lawful purpose of self-defense. Under any of the standards of scrutiny the Court has applied to enumerated constitutional rights, this prohibition—in the place where the importance of the lawful defense of self, family, and property is most acute—would fail constitutional muster. Similarly, the requirement that any lawful firearm in the home be disassembled or bound by a trigger lock makes it impossible for citizens to use arms for the core lawful purpose of self-defense and is hence unconstitutional. Because Heller conceded at oral argument that the D. C. licensing law is permissible if it is not enforced arbitrarily and capriciously, the Court assumes that a license will satisfy his prayer for relief and does not address the licensing requirement. Assuming he is not disqualified from exercising Second Amendment rights, the District must permit Heller to register his handgun and must issue him a license to carry it in the home. Pp. 56-64. 478 F. 3d 370, affirmed. Scalia, J., delivered the opinion of the Court, in which Roberts, C. J., and Kennedy, Thomas, and Alito, JJ., joined. Stevens, J., filed a dissenting opinion, in which Souter, Ginsburg, and Breyer, JJ., joined. Breyer, J., filed a dissenting opinion, in which Stevens, Souter, and Ginsburg, JJ., joined. DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA, et al., PETITIONERS On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals [June 26, 2008] Justice Scalia delivered the opinion of the Court.

Nothing uncommon or unusual about an AR-15, the police have one in the trunk, a semi-automatic pistol in the holster and a shotgun in the rack. So the government can regulate fully automatic weapons. They shouldn't be taxing ammunition, reloading tools or disallowing magazine sizes. Anymore than they should be outlawing training or shooting ranges.

THIS IS A TAG LINE...Exercising rights is only radical to two people, Tyrants and Slaves. Which are YOU? Our ignorance has driven us into slavery and we do not recognize it.

I was relieved to see that Cabela’s sells them all. https://www.cabelas.com/category/Semiautomatic-Pistols/105529680.uts https://www.cabelas.com/browse.cmd?categoryId=734095080&CQ_search=shotguns&CQ_zstype=REG https://www.cabelas.com/browse.cmd?categoryId=734095080&CQ_search=ar-15&CQ_zstype=REG What the government should, or should not, do does not define what the government has the power to do. Fact, the government may and does tax food. There is nothing to prevent the government from taxing ammunition. Power is power. The guy who created the Internal Revenue and initated the unapportioned income tax became a national hero carved into Mt. Rushmore. Nobody has outlawed firearms training or shooting ranges. Some jackasses are pandering to the radical left during an election cycle. Others are pandering to the radical right. Any such bill, if signed into law, would be subject to an immediate restraining order, followed up by being struck down as unconstitutional.

There is sales tax on store sales, adding a special tax on ammo above and beyond that would define an infringement as much as a poll tax would. The same goes for loading tools and equipment. Tax the sales, a special tax is an obvious attempt to make it harder to exercise the RKBA.

THIS IS A TAG LINE...Exercising rights is only radical to two people, Tyrants and Slaves. Which are YOU? Our ignorance has driven us into slavery and we do not recognize it.

There is a tax on practically everything, including food. In many states, prescription drugs are taxed. Income is taxed. Various Nevada locations have taxed sex at brothels, interfering with the right to get laid. The right to keep and bear arms does not guarantee you may do it tax free.

Dubious, indeed. Jefferson wanted the include the phrase “No free man shall ever be debarred the use of arms” in the proposed Virginia State constitution in 1776. It was rejected.

Jesus. How in the hell did they ever come up with that little ditty? I suppose the second amendment's mention of a militia was superfluous. So simple. The second amendment protects state militias from federal infringement and state constitutions protect the individual right.

US v Miller does NOT say "those in common use for lawful purposes". It reads "of the kind in common use at the time". Period. But the rest is correct -- the second amendment protects only militia-type weapons.

Miller said nothing about "prohibiting the carrying of dangerous and unusual weapons". Quite the contrary. Miller said the second amendment ONLY protects militia-type weapons. If militia-type weapons (eg., machine guns) are banned, how are they ever to become "in common use"?

Correct. According to Miller, the weapon had to have "some reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia”. Weapons of war were protected by the second amendment.

The drafting history is of dubious interpretative worth as it does not express the will of the legislative body

No bother, the English Common Law, from which the right to keep and bear arms was directly derived, contains the content you question. But the amendment says "the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed." What is it that shall not be infringed? One needs to determine what was intended by the term "the right of the people to keep and bear arms" to determine what shall not be infringed. As stated in 1802 and quoted in Lynch v. Clarke in 1844, "The constitution is unintelligible without reference, to the common law." By the interpretation of some, one must find the Framers intended to protect, and did protect, a right that did not then exist and had never existed in the colonies, the several states or the United States. It was the colonial common law right to keep and bear arms that was carried forth into the union. Lynch v. Clarke, New York Legal Observer, Vol 3, 236, 245 (1844) Quotes from State Constitutions Paragraph 1. Be it enacted and declared by the Governor, and Council, and House of Representatives, in General Court assembled, That the ancient Form of Civil Government, contained in the Charter from Charles the Second, King of England, and adopted by the People of this State, shall be and remain the Civil Constitution of this State, under the sole authority of the People thereof, independent of any King or Prince whatever. - - - - - Delaware 1776 Art. 25. The common law of England, as well as so much of the statute law as has been heretofore adopted in practice in this State, shall remain in force, unless they shall be altered by a future law of the legislature; such parts only excepted as are repugnant to the rights and privileges contained in this constitution, and the declaration of rights, &c., agreed to by this convention. - - - - - Maryland, 1776 III. That the inhabitants of Maryland are entitled to the common law of England, and the trial by jury, according to the course of that law, and to the benefit of such of the English statutes, as existed at the time of their first emigration, and which, by experience, have been found applicable to their local and other circumstances, and of such others as have been since made in England, or Great Britain, and have been introduced, used and practised by the courts of law or equity; and also to acts of Assembly, in force on the first of June seventeen hundred and seventy-four, except such as may have since expired, or have been or may be altered by acts of Convention, or this Declaration of Rights—subject, nevertheless, to the revision of, and amendment or repeal by, the Legislature of this State: and the inhabitants of Maryland are also entitled to all property, derived to them, from or under the Charter, granted by his Majesty Charles I. to Cæcilius Calvert, Baron of Baltimore. - - - - - New Jersey, 1776 XXI. That all the laws of this Province, contained in the edition lately published by Mr. Allinson, shall be and remain in full force, until altered by the Legislature of this Colony (such only excepted, as are incompatible with this Charter) and shall be, according as heretofore, regarded in all respects, by all civil officers, and others, the good people of this Province. XXII. That the common law of England, as well as so much of the statute law, as have been heretofore practised in this Colony, shall still remain in force, until they shall be altered by a future law of the Legislature; such parts only excepted, as are repugnant to the rights and privileges contained in this Charter; and that the inestimable right of trial by jury shall remain confirmed as a part of the law of this Colony, without repeal, forever. - - - - - New York, 1777 XXXV. And this convention doth further, in the name and by the authority of the good people of this State, ordain, determine, and declare that such parts of the common law of England, and of the state law of England and Great Britain, and of the acts of the legislature of the colony of New York, as together did form the law of the said colony on the 19th day of April, in the year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and seventy-five, shall be and continue the law of this State, subject to such alterations and provisions as the legislature of this State shall, from time to time, make concerning the same. That such of the said acts, as are temporary, shall expire at the times limited for their duration respectively. That all such parts of the said common law, and all such of the said statutes and acts aforesaid, or parts thereof, as may be construed to establish or maintain any particular denomination of Christians or their ministers, or concern the allegiance heretofore yielded to, and the supremacy, sovereignty, government, or prerogatives claimed or exercised by, the King of Great Britain and his predecessors, over the colony of New York and its inhabitants, or are repugnant to this constitution, be, and they hereby are, abrogated and rejected. And this convention doth further ordain, that the resolves or resolutions of the congresses of the colony of New York, and of the convention of the State of New York, now in force, and not repugnant to the government established by this constitution, shall be considered as making part of the laws of this State; subject, nevertheless, to such alterations and provisions as the legislature of this State may, from time to time, make concerning the same. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/blackstone_bk1ch1.asp Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England Book the First - Chapter the First: Of the Absolute Rights of Individuals (1765)

It is about time you get past Miller and the transportation of a sawed off shotgun. Update to Heller and McDonald.

Update to where you can say according to Heller and McDonald.

The second amendment protects the right to bear arms. It shall not be infringed. That means you can have any weapon you want. That is what the words mean. Now what some hack Judge like Roberts says.

Exactly. And that was the right of the states to form militias and to have that right protected from federal infringement.

That's like saying, "Update to Roe v Wade" or "Update to Kelo". Heller and McDonald are flawed rulings. They're contrary to all previous rulings by the courts and contrary to the Framer's intent. State constitutions protect the individual right to keep and bear arms -- -- -- which is why gun laws vary from state to state.

Heller cited Miller so why can't I?

The second amendment protected the right of "the people" as part of a State militia to keep and bear militia-type weapons from federal infringement. That's the way it was written and that's the way it was interpreted by the courts for over 200 years.

[misterwhite #28] Heller cited Miller so why can't I? [misterwhite #29] The second amendment protected the right of "the people" as part of a State militia to keep and bear militia-type weapons from federal infringement. While Miller does not really conflict with Heller, Heller, as the more recent interpretation of the Constitution, strikes down all prior interpretations which conflict with Heller. Heller applied to the District of Columbia. McDonald extended the application of Heller to the States. They are binding precedent, whether you agree with them or not. Miller, does not conflict with Heller, as Heller interprets Miller. You may cite Miller as in agreement with Heller. Any of your misbegotten fanciful interpretations of Miller are non-starters as being in conflict with Heller. Any holding of constitutional interpretation in Miller which actually conflicted with Heller would be struck down by Heller. To cite Miller to interpret the Constitution in a fashion in conflict with Heller is an act of futility and a waste of time. The law of the United States, as expressed in Heller: SCALIA, J., delivered the opinion of the Court, in which Roberts, C.J. and Kennedy, Thomas, and Alito, JJ., joined. District of Columbia v. Heller 554 U.S. 570 (2008) at 620-28: Presser v. Illinois, 116 U. S. 252 (1886), held that the right to keep and bear arms was not violated by a law that forbade "bodies of men to associate together as military organizations, or to drill or parade with arms in cities and towns unless authorized by law." Id., at 264-265. This does not refute the individual-rights interpretation of the Amendment; no one supporting that interpretation has contended that States may not ban such groups. JUSTICE STEVENS [621] presses Presser into service to support his view that the right to bear arms is limited to service in the militia by joining Presser's brief discussion of the Second Amendment with a later portion of the opinion making the seemingly relevant (to the Second Amendment) point that the plaintiff was not a member of the state militia. Unfortunately for JUSTICE STEVENS' argument, that later portion deals with the Fourteenth Amendment; it was the Fourteenth Amendment to which the plaintiff's nonmembership in the militia was relevant. Thus, JUSTICE STEVENS' statement that Presser "suggested that . . . nothing in the Constitution protected the use of arms outside the context of a militia," post, at 674-675, is simply wrong. Presser said nothing about the Second Amendment's meaning or scope, beyond the fact that it does not prevent the prohibition of private paramilitary organizations. JUSTICE STEVENS places overwhelming reliance upon this Court's decision in Miller, 307 U. S. 174. "[H]undreds of judges," we are told, "have relied on the view of the Amendment we endorsed there," post, at 638, and "[e]ven if the textual and historical arguments on both sides of the issue were evenly balanced, respect for the well-settled views of all of our predecessors on this Court, and for the rule of law itself . . . would prevent most jurists from endorsing such a dramatic upheaval in the law," post, at 639. And what is, according to JUSTICE STEVENS, the holding of Miller that demands such obeisance? That the Second Amendment "protects the right to keep and bear arms for certain military purposes, but that it does not curtail the Legislature's power to regulate the nonmilitary use and ownership of weapons." Post, at 637. Nothing so clearly demonstrates the weakness of JUSTICE STEVENS' case. Miller did not hold that and cannot possibly be read to have held that. The judgment in the case upheld against a Second Amendment challenge two men's federal indictment for transporting an unregistered short-barreled [622] shotgun in interstate commerce, in violation of the National Firearms Act, 48 Stat. 1236. It is entirely clear that the Court's basis for saying that the Second Amendment did not apply was not that the defendants were "bear[ing] arms" not "for . . . military purposes" but for "nonmilitary use," post, at 637. Rather, it was that the type of weapon at issue was not eligible for Second Amendment protection: "In the absence of any evidence tending to show that the possession or use of a [short-barreled shotgun] at this time has some reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia, we cannot say that the Second Amendment guarantees the right to keep and bear such an instrument." 307 U. S., at 178 (emphasis added). "Certainly," the Court continued, "it is not within judicial notice that this weapon is any part of the ordinary military equipment or that its use could contribute to the common defense." Ibid. Beyond that, the opinion provided no explanation of the content of the right. This holding is not only consistent with, but positively suggests, that the Second Amendment confers an individual right to keep and bear arms (though only arms that "have some reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia"). Had the Court believed that the Second Amendment protects only those serving in the militia, it would have been odd to examine the character of the weapon rather than simply note that the two crooks were not militiamen. JUSTICE STEVENS can say again and again that Miller did not "turn on the difference between muskets and sawed-off shotguns; it turned, rather, on the basic difference between the military and nonmilitary use and possession of guns," post, at 677, but the words of the opinion prove otherwise. The most JUSTICE STEVENS can plausibly claim for Miller is that it declined to decide the nature of the Second Amendment right, despite the Solicitor General's argument (made in the alternative) that the right was collective, see Brief for United States, O. T. 1938, [623] No. 696, pp. 4-5. Miller stands only for the proposition that the Second Amendment right, whatever its nature, extends only to certain types of weapons. It is particularly wrongheaded to read Miller for more than what it said, because the case did not even purport to be a thorough examination of the Second Amendment. JUSTICE STEVENS claims, post, at 676-677, that the opinion reached its conclusion "[a]fter reviewing many of the same sources that are discussed at greater length by the Court today." Not many, which was not entirely the Court's fault. The defendants made no appearance in the case, neither filing a brief nor appearing at oral argument; the Court heard from no one but the Government (reason enough, one would think, not to make that case the beginning and the end of this Court's consideration of the Second Amendment). See Frye, The Peculiar Story of United States v. Miller, 3N. Y. U. J. L. & Liberty 48, 65-68 (2008). The Government's brief spent two pages discussing English legal sources, concluding "that at least the carrying of weapons without lawful occasion or excuse was always a crime" and that (because of the class-based restrictions and the prohibition on terrorizing people with dangerous or unusual weapons) "the early English law did not guarantee an unrestricted right to bear arms." Brief for United States, O. T. 1938, No. 696, at 9-11. It then went on to rely primarily on the discussion of the English right to bear arms in Aymette v. State, 21 Tenn. 154, for the proposition that the only uses of arms protected by the Second Amendment are those that relate to the militia, not self-defense. See Brief for United States, O. T. 1938, No. 696, at 12-18. The final section of the brief recognized that "some courts have said that the right to bear arms includes the right of the individual to have them for the protection of his person and property," and launched an alternative argument that "weapons which are commonly used by criminals," such as sawed-off shotguns, are not protected. See id., at 18-21. The Government's Miller brief thus provided [624] scant discussion of the history of the Second Amendment—and the Court was presented with no counterdiscussion. As for the text of the Court's opinion itself, that discusses none of the history of the Second Amendment. It assumes from the prologue that the Amendment was designed to preserve the militia, 307 U. S., at 178 (which we do not dispute), and then reviews some historical materials dealing with the nature of the militia, and in particular with the nature of the arms their members were expected to possess, id., at 178-182. Not a word (not a word) about the history of the Second Amendment. This is the mighty rock upon which the dissent rests its case. We may as well consider at this point (for we will have to consider eventually) what types of weapons Miller permits. Read in isolation, Miller's phrase "part of ordinary military equipment" could mean that only those weapons useful in warfare are protected. That would be a startling reading of the opinion, since it would mean that the National Firearms Act's restrictions on machineguns (not challenged in Miller) might be unconstitutional, machineguns being useful in warfare in 1939. We think that Miller's "ordinary military equipment" language must be read in tandem with what comes after: "[O]rdinarily when called for [militia] service [able-bodied] men were expected to appear bearing arms supplied by themselves and of the kind in common use at the time." 307 U. S., at 179. The traditional militia was formed from a pool of men bringing arms "in common use at the time" for lawful purposes like self-defense. "In the colonial [625] and revolutionary war era, [small-arms] weapons used by militiamen and weapons used in defense of person and home were one and the same." State v. Kessler, 289 Ore. 359, 368, 614 P. 2d 94, 98 (1980) (citing G. Neumann, Swords and Blades of the American Revolution 6-15, 252-254 (1973)). Indeed, that is precisely the way in which the Second Amendment's operative clause furthers the purpose announced in its preface. We therefore read Miller to say only that the Second Amendment does not protect those weapons not typically possessed by law-abiding citizens for lawful purposes, such as short-barreled shotguns. That accords with the historical understanding of the scope of the right, see Part III, infra. 25 We conclude that nothing in our precedents forecloses our adoption of the original understanding of the Second Amendment. [...] [626] III Like most rights, the right secured by the Second Amendment is not unlimited. From Blackstone through the 19th-century cases, commentators and courts routinely explained that the right was not a right to keep and carry any weapon whatsoever in any manner whatsoever and for whatever purpose. See, e.g., Sheldon, in 5 Blume 346; Rawle 123; Pomeroy 152-153; Abbott 333. For example, the majority of the 19th-century courts to consider the question held that prohibitions on carrying concealed weapons were lawful under the Second Amendment or state analogues. See, e.g., State v. Chandler, 5 La. Ann., at 489-490; Nunn v. State, 1 Ga., at 251; see generally 2 Kent *340, n. 2; The American Students' Blackstone 84, n. 11 (G. Chase ed. 1884). Although we do not undertake an exhaustive historical analysis today of the full scope of the Second Amendment, nothing in our opinion should be taken to cast doubt on longstanding prohibitions on the possession of firearms by felons and the mentally ill, or laws forbidding the carrying of firearms in sensitive places such as schools and government buildings, or laws impos- [627] ing conditions and qualfications on the commercial sale of arms. We also recognize another important limitation on the right to keep and carry arms. Miller said, as we have explained, that the sorts of weapons protected were those "in common use at the time." 307 U. S., at 179. We think that limitation is fairly supported by the historical tradition of prohibiting the carrying of "dangerous and unusual weapons." See 4 Blackstone 148-149 (1769); 3 B. Wilson, Works of the Honourable James Wilson 79 (1804); J. Dunlap, The New York Justice 8 (1815); C. Humphreys, A Compendium of the Common Law in Force in Kentucky 482 (1822); 1 W. Russell, A Treatise on Crimes and Indictable Misdemeanors 271-272 (1831); H. Stephen, Summary of the Criminal Law 48 (1840); E. Lewis, An Abridgment of the Criminal Law of the United States 64 (1847); F. Wharton, A Treatise on the Criminal Law of the United States 726 (1852). See also State v. Langford, 10 N. C. 381, 383-384 (1824); O'Neill v. State, 16 Ala. 65, 67 (1849); English v. State, 35 Tex. 473, 476 (1871); State v. Lanier, 71 N. C. 288, 289 (1874). It may be objected that if weapons that are most useful in military service—M-16 rifles and the like—may be banned, then the Second Amendment right is completely detached from the prefatory clause. But as we have said, the conception of the militia at the time of the Second Amendment's ratiication was the body of all citizens capable of military service, who would bring the sorts of lawful weapons that they possessed at home to militia duty. It may well be true today that a militia, to be as effective as militias in the 18th century, would require sophisticated arms that are highly unusual in society at large. Indeed, it may be true that no amount of small arms could be useful against modern-day bombers and tanks. But the fact that modern developments have limited the degree of it between the prefatory clause [628] and the protected right cannot change our interpretation of the right.

Miller protected militia-type weapons from federal infringement. Heller ruled that "common use" weapons are protected for self-defense in the home. Totally different, a perversion of the second amendment, and a ruling which limits second amendment protection. "They are binding precedent, whether you agree with them or not." I see. They're binding, but Cruikshank, Presser and Miller are not.

Oh? And where is that enumerated power listed in the U.S. Constitution? "Had the Court believed that the Second Amendment protects only those serving in the militia, it would have been odd to examine the character of the weapon rather than simply note that the two crooks were not militiamen." Pure speculation. The Miller court ruled on the weapon being transported in interstate commerce and found that the second amendment did not protect it -- no matter who was transporting it.

Might be unconstitutional? The National Firearms Act's restrictions on machineguns ARE unconstitutional. And without those restrictions, machine guns WOULD be "in common use" today.

Anywhere that you project that Miller interpreted the Constitution differently than Heller, Miller is superseded by Heller. Your attempts to invoke Miller are futile and a waste of time. On any particular point, a more recent holding supersedes any prior holding. If you wish to continue your misinterpretation of Miller you are free to do so. Heller said there was no conflict. If there were a conflict, Heller would supercede Miller or any prior precedent you may choose to drag up or misinterpret.

Anywhere that you project that Miller interpreted the Constitution differently than Heller, Miller is superseded by Heller. Your attempts to invoke Miller are futile and a waste of time. On any particular point, a more recent holding supersedes any prior holding. If you wish to continue your misinterpretation of Miller you are free to do so. Heller said there was no conflict. If there were a conflict, Heller would supercede Miller or any prior precedent you may choose to drag up or misinterpret.

Nope it is an individual right. The right of the people to keep and bear arms. You're wrong like you often are. If you get confused again just let me know and I will set you straight.

Case law is a waste of time. It isn't in the constitution. Read the constitution and understand it for yourself instead of relying on tyrants. If they get it right give them kudos. If they get it wrong don't pretend and do mental gymnastics to make words mean things they never said. It must stuck to have to change the meaning of words based on what some judge says.

Sure, if you ignore the rest of the amendment.

Stare decisis be damned!

Stare decisis be damned!

The Constitution itself is drafted in the language of the English Common Law and SCOTUS itself has remarked that it is impossible to read and interpret without resort to the English Common Law. Common law itself is the collection of court-made law. If you do not like the common law system, you should experience just one case in the Code System of law, common in Latin Europe. Case law is the very basis of the Common Law system of law adopted by the Federal government and all thirteen original States. All thirteen states adopted so much of the English Common Law as was not inconsistent with the Federal Consistution. They did so explicitly, either in their State constitution, or in their State statute law. You need not take my word for it. Long ago, I collected the source material for that claim and published it on scribd. Absent stare decisis, we would not have a functioning legal system at all.

See #41 and stop being a jerk.

Me being a jerk? You lecture me on stare decisis while ignoring Cruikshank, Presser and Miller? Then you have the balls to say that, well, if there is a conflict with Heller, too bad. Heller is now the new precedent and I must ignore all prior rulings ... because stare decisis. You want to give this power to the Supreme Court? The power, for example, to define the type of arms protected and have that definition apply nationwide? Already they've limited the definition to "in common use" for self-defense in the home. Yeah, that's what the second amendment means. You're so eager to look to the U.S. Supreme Court to protect this right from state laws that you ignore the potential for abuse by some future, liberal-dominated court which now has the power to destroy the real meaning.

Then you have the balls to say that, well, if there is a conflict with Heller, too bad. Heller is now the new precedent and I must ignore all prior rulings ... because stare decisis. Yes, that's how it works. When Brown v. Topeka Board of Education struck down Plessey v. Ferguson, neither Plessey nor anything else could be cited as making separate but equal lawful. Repeating your bullshit endlessly does not polish those turds of thought into pearls of wisdom. Heller and McDonald superseded all prior interpretations which conflicted with them. Heller states it did not conflict earlier precedents. Heller disagrees with your personal and very fanciful, but wrong, reading of those precedents. Your personal, but wrong, reading of those precedents does not strike down Heller. Deal with it. Heller does not conflict with earlier precedent. If there were an earlier precedent in conflict, Heller would supersede it. As for the actual law, can you go out and lawfully purchase a newly manufactured machine gun, or can't you?

No. Only an existing one at an exorbitant price.

No. Only an existing one at an exorbitant price. Has it been that way since before you were born?

1986 federal legislation called the Firearm Owners Protection Act (specifically the Hughes Amendment) prohibited the possession of “new” machine guns by citizens.

Firearm Owners Protection Act of 1986. Signed into law 19 March 1986. Which commie was president then? Passed in the Senate 79-15. The yeas were 49 GOP, 30 Dem. The Nays were 2 GOP, 13 Dem. Not voting 2 GOP, 4 Dem. Passed in the House (amended) by voice vote. Agreed to in the Senate by voice vote.

Yep. Usually how controversial and unconstitutional laws are passed. No individual accountability.

Accurate. You accurately portray the legal system as it is, and particularly the system of precedent as it applies under the Common Law. I've practiced both American law (common law) and French Civil Law. The systems get to about the same conclusions, but the pathways are different. That they arrive at the same place is testimony to the bedrock of COMMON SENSE that underlies law. Law is not an exercise in abstract philosophy. It is, in the final analysis, a TOOL of governance, where the rubber meets the road between actual citizens in real disputes with each other and/or with the state. Nutty notions that some subject matter is, somehow, "above the law" just don't work in a world in which there are REAL disputes, with REAL economic and physical consequences. The reason we developed courts at all - whether Common Law or Civil Law - is precisely because if such places of official adjudication DON'T exist and DON'T have orderly rules and procedures that can be predicted and relied upon, people will resort to "self-help", which is a nice way of saying dueling, blood feud, vendetta, and private war. Civil Law, originally Roman Law, fell into disrepair after the fall of Rome, and with it, the Roman Peace evaporated. Feudal Europe was a pretty bloody and terrible place to live. Common Law grew up in places as a bulwark against the craziness of blood feud. Granted, Christianity (specifically Catholic Canon Law, which was the only game in town in the 1000s (crazies' assertions to the contrary notwithstanding), very heavily inflected the civil and common law courts, by providing an overarching set of lofty (and often unachieved) standards. Still, courts evolved through experience and common sense. People having the "God-given right" to carry around unregistered machine guns, set up AA missile batteries in their yards on short final to JFK airport, and keeping a stock of mustard gas and a nuke in their basement, "just in case" cannot be what the Second Amendment means. The Constitution is not a suicide pact!

People have a "God-given right" to self-defense. Beyond that, it's up to the law.

Oh? The system that says if you don't like precedent you can change it? Then once you have the new "precedent" you're happy with, that precedent cannot be changed because shut up.

Hold 'em accountable. Them and President Ronald Reagan. Senate Vote #142 1985-07-09 TO PASS S 49

REPUBLICAN - YEA

SD Yea Sen. James Abdnor [R, 1981-1986]

ND Yea Sen. Mark Andrews [R, 1981-1986]

MN Yea Sen. Rudolph "Rudy" Boschwitz [R, 1978-1990]

MS Yea Sen. Thad Cochran [R, 1979-2018]

ME Yea Sen. William Cohen [R, 1979-1996]

NY Yea Sen. Alfonse D'Amato [R, 1981-1998]

MO Yea Sen. John Danforth [R, 1976-1994]

AL Yea Sen. Jeremiah Denton Jr. [R, 1981-1986]

KS Yea Sen. Robert Dole [R, 1969-1996]

NM Yea Sen. Pete Domenici [R, 1973-2008]

MN Yea Sen. David Durenberger [R, 1978-1994]

NC Yea Sen. John East [R, 1981-1986]

WA Yea Sen. Daniel Evans [R, 1983-1988]

UT Yea Sen. Edwin "Jake" Garn [R, 1974-1992]

AZ Yea Sen. Barry Goldwater [R, 1969-1986]

WA Yea Sen. Slade Gorton [R, 1981-1986]

TX Yea Sen. Phil Gramm [R, 1985-2002]

IA Yea Sen. Charles "Chuck"Grassley [R, 1981-2022]

UT Yea Sen. Orrin Hatch [R, 1977-2018]

FL Yea Sen. Paula Hawkins [R, 1981-1986]

NV Yea Sen. Jacob Hecht [R, 1983-1988]

PA Yea Sen. Henry Heinz III [R, 1977-1991]

NC Yea Sen. Jesse Helms [R, 1973-2002]

NH Yea Sen. Gordon Humphrey [R, 1979-1990]

KS Yea Sen. Nancy Kassebaum [R, 1978-1996]

WI Yea Sen. Robert Kasten Jr. [R, 1981-1992]

NV Yea Sen. Paul Laxalt [R, 1974-1986]

IN Yea Sen. Richard Lugar [R, 1977-2012]

GA Yea Sen. Mack Mattingly [R, 1981-1986]

ID Yea Sen. James McClure [R, 1973-1990]

KY Yea Sen. Mitch McConnell [R, 1985-2020]

AK Yea Sen. Frank Murkowski [R, 1981-2002]

OK Yea Sen. Don Nickles [R, 1981-2004]

OR Yea Sen. Robert Packwood [R, 1969-1995]

SD Yea Sen. Larry Pressler [R, 1979-1996]

IN Yea Sen. James "Dan" Quayle [R, 1981-1989]

DE Yea Sen. William Roth Jr. [R, 1971-2000]

NH Yea Sen. Warren Rudman [R, 1980-1992]

WY Yea Sen. Alan Simpson [R, 1979-1996]

PA Yea Sen. Arlen Specter [R, 1981-2010]

VT Yea Sen. Robert Stafford [R, 1971-1988]

AK Yea Sen. Ted Stevens [R, 1968-2008]

ID Yea Sen. Steven Symms [R, 1981-1992]

SC Yea Sen. Strom Thurmond [R, 1956-2002]

VA Yea Sen. Paul Trible Jr. [R, 1983-1988]

VA Yea Sen. Paul Trible Jr. [R, 1983-1988]

WY Yea Sen. Malcolm Wallop [R, 1977-1994]

WY Yea Sen. Malcolm Wallop [R, 1977-1994]

VA Yea Sen. John Warner [R, 1979-2008]

CT Yea Sen. Lowell Weicker Jr. [R, 1971-1988]

CA Yea Sen. Pete Wilson [R, 1983-1991]

DEMOCRAT - YEA

MT Yea Sen. Max Baucus [D, 1978-2014]

DE Yea Sen. Joseph Biden Jr. [D, 1973-2009]

NM Yea Sen. Jeff Bingaman [D, 1983-2012]

WV Yea Sen. Robert Byrd [D, 1959-2010]

TX Yea Sen. Lloyd Bentsen Jr. [D, 1971-1993]

OK Yea Sen. David Boren [D, 1979-1994]

AR Yea Sen. Dale Bumpers [D, 1975-1998]

ND Yea Sen. Quentin Burdick [D, 1960-1992]

FL Yea Sen. Lawton Chiles Jr. [D, 1971-1988]

AZ Yea Sen. Dennis DeConcini [D, 1977-1994]

IL Yea Sen. Alan Dixon [D, 1981-1992]

MO Yea Sen. Thomas Eagleton [D, 1968-1986]

NE Yea Sen. James Exon [D, 1979-1996]

KY Yea Sen. Wendell Ford [D, 1974-1998]

OH Yea Sen. John Glenn Jr. [D, 1974-1998]

TN Yea Sen. Albert Gore Jr. [D, 1985-1992]

IA Yea Sen. Thomas "Tom" Harkin [D, 1985-2014]

AL Yea Sen. Howell Heflin [D, 1979-1996]

SC Yea Sen. Ernest "Fritz" Hollings [D, 1966-2004]

LA Yea Sen. John Johnston Jr. [D, 1972-1996]

VT Yea Sen. Patrick Leahy [D, 1975-2022]

MT Yea Sen. John Melcher [D, 1977-1988]

ME Yea Sen. George Mitchell [D, 1980-1994]

GA Yea Sen. Samuel Nunn [D, 1972-1996]

WI Yea Sen. William Proxmire [D, 1957-1988]

AR Yea Sen. David Pryor [D, 1979-1996]

MI Yea Sen. Donald Riegle Jr. [D, 1977-1994]

WV Yea Sen. John "Jay" Rockefeller IV [D.1985-2014]

TN Yea Sen. James Sasser [D, 1977-1994]

NE Yea Sen. Edward Zorinsky [D, 1976-1987]

REPUBLICAN - NAY

RI Nay Sen. John Chafee [R, 1976-1999]

MD Nay Sen. Charles Mathias Jr. [R, 1969-1986]

DEMOCRAT - NAY

CT Nay Sen. Christopher Dodd [D, 1981-2010]

HI Nay Sen. Daniel Inouye [D, 1963-2012]

MA Nay Sen. Edward "Ted" Kennedy [D, 1962-2009]

MA Nay Sen. John Kerry [D, 1985-2013]

NJ Nay Sen. Frank Lautenberg [D, 1982-2000]

MI Nay Sen. Carl Levin [D, 1979-2014]

MD Nay Sen. Paul Sarbanes [D, 1977-2006]

NY Nay Sen. Daniel Moynihan [D, 1977-2000]

CA Nay Sen. Alan Cranston [D, 1969-1992]

CO Nay Sen. Gary Hart [D, 1975-1986]

HI Nay Sen. Spark Matsunaga [D, 1977-1990]

OH Nay Sen. Howard Metzenbaum [D, 1976-1994]

RI Nay Sen. Claiborne Pell [D, 1961-1996]

REPUBLICAN - NOT VOTING

CO NV Sen. William Armstrong [R, 1979-1990]

CO NV Sen. Mark Hatfield [R, 1967-1996]

DEMOCRAT - NOT VOTING

NJ NV Sen. William "Bill" Bradley [D, 1979-1996]

LA NV Sen. Russell Long [D, 1948-1986]

IL NV Sen. Paul Simon [D, 1985-1996]

MS NV Sen. John Stennis [D, 1947-1988]

Do Catholics, Protestants, Jews, Muslims, and Hindus have the same God-given rights recognized by the U.S. justice system? Do athiests have God-given rights recognized by the U.S. justice system? What does the U.S. justice system consult to determine which rights are given by God Hisself? Whose God is considered the Giver? Does it matter whether the judge is a Catholic, Protestant, Jew, Muslim, or athiest? Or does the U.S. justice system recognize the common law right of self-defense?

While the right to keep and bear arms may not be infringed, the right as brought forth from the English common law into the colonies and into the States, has inherent limitations. These limitations are part of the right, they define the right, they do not infringe upon the right. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/blackstone_bk1ch1.asp Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England Book the First - Chapter the First: Of the Absolute Rights of Individuals (1765) It has never meant a right to carry any and all weapons for any purpose. It does not mean that today.

The Hughes Amendment was a voice vote. It sounded like the Nays had it, but Rangel said the Ayes had it and refused a recorded vote.

Then once you have the new "precedent" you're happy with, that precedent cannot be changed because shut up. Yes, precedent can be changed. Were SCOTUS to issue an opinion that abortion was infanticide, and not a constitutionally protected right, Roe could no longer be cited to the effect that abortion is a constitutional right. The more recent precedent would prevail. A prevailing precedent can be changed by amending the constitution. Opinions in Scott v. Sandford were not judicially overturned, but were overturned by post-war amendments which changed the law. As an historical note, SCOTUS found that it lacked jurisdiction to hear the case, that the lower court also lacked jurisdiction to hear the case, and SCOTUS remanded the case to the lower court with instructions to dismiss the case for lack of jurisdiction. Minor v. Happersett in 1875 held unanimously that women did not have a constitutional right to vote for President. Moreover, neither did anyone else, and they still don't. But the 19th Amendment came along and said, "The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex." Women may not be denied the right to vote because of their sex. Where men are allowed to vote, women must be allowed to vote on an equal basis. Minor was correctly decided according to the law then in existence, so the law was changed. A new abortion precedent could be changed by having the issue revisited by the Court yet again, and changing its interpretation of the Constitution. Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896 held that seperate but equal was constitutional. Brown v. Topeka Board of Education in 1954 revisited the issue and held that seperate but equal was inherently unequal and was unconstitutional. One cannot go to court and argue Plessy as precedent to overturn Brown. What cannot be done is to cite a perceived conflict between Miller (1939)and Heller/McDonald (2008/2010) and claim Miller supersedes the more recent interpretation of the Constitution in Heller/McDonald. The precedent set by Heller/McDonald can be overturned by a subsequent, more recent interpretation by the U.S. Supreme Court. Should the Court issue a holding in misterwhite v United States, (2020) saying that the 2nd Amendment protects the right to own a newly manufactured machine gun, you would have a new precedent and could buy all the new machine guns you want. Until the Constitution is amended, or the Supreme Court revisits the issue, you are out of luck.

The Declaration of Independence declared that "all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights , that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness". The right to self- defense is part of the right to life. Now, if the right to self-defense includes the right to own an AK-47, then we would all have the right to own an AK-47. Correct? Even 12-year-olds? Certainly you wouldn't deny the right to self-defense to a 12-year-old!

I'm not saying Miller supercedes anything. I'm citing the doctrine of precedent -- stare decisis -- which Heller totally ignored. Miller concluded the only arms protected by the second amendment were militia-type arms. That was ignored by Heller because it didn't fit their in-common-use-for-self-defense-in-the-home made-up interpretation.

The House vote to approve the Hughes Amendment to the Bill was a Record Vote 286-136. The House vote to approve the bill as amended, including the Hughes Amendment, was a Record Vote 292-130. - - - - - - - - - - https://www.congress.gov/bill/99th-congress/house-bill/4332/titles Short Titles Short Titles as Passed House Short Titles as Reported to House Short Titles as Introduced Official Titles Official Title as Introduced https://www.congress.gov/bill/99th-congress/house-bill/4332/actions 03/14/1986 Reported to House (Amended) by House Committee on The Judiciary. Report No: 99-495. 03/06/1986 Introduced in House - - - - - - - - - - https://www.congress.gov/bill/99th-congress/house-bill/4332 (Reported to House from the Committee on the Judiciary with amendment, H. Rept. 99-495) Federal Firearms Law Reform Act of 1986 - Amends the Gun Control Act of 1968 to prohibit the transfer or possession of silencers. Permits the interstate sale of rifles and shotguns, provided: (1) the transferee and the transferor meet in person to accomplish the transfer; and (2) the sale, delivery, and receipt comply with the legal conditions of sale in both States. Makes it unlawful for any person to sell or ship any firearm or ammunition to someone who: (1) is under indictment for, or has been convicted of, a felony; (2) is a fugitive from justice; (3) is an unlawful user of or addicted to a controlled substance; (4) has been adjudicated as a mental incompetent or committed to a mental institution; (5) has received a dishonorable discharge from the armed forces; (6) has renounced his U.S. citizenship; or (7) is an illegal alien. Makes it unlawful for such persons to receive, possess, or transfer any firearm or ammunition in interstate or foreign commerce. Permits gun sales at certain gun shows. Prohibits the importation of the barrel of any firearm if the importation of that firearm is prohibited. Revises the criteria reviewed by the Secretary of the Treasury in approving applications for licenses. Grants the Secretary authority to suspend (rather than just revoke) a license. Allows the Secretary to inspect the inventory and records of a licensee to ensure compliance with the recordkeeping requirements of such Act. Modifies the penalty provisions for certain licensee violations. Eliminates the recordkeeping requirements for ammunition sales involving less than 1,000 rounds. Codifies existing regulations requiring reports of multiple firearm sales. Establishes additional mandatory penalties for the use or carrying of firearms or armor-piercing ammunition during certain drug trafficking activities. Imposes additional mandatory penalties for machine gun use in crimes. Limits to felony violations the Government's authority to seize firearms and ammunition. Allows individuals who have violated the Gun Control Act of 1968 or the National Firearms Act to apply for relief from the legal disabilities imposed by such statutes. Authorizes the Secretary to grant such relief. Allows the interstate transport of rifles and shotguns by individuals under certain circumstances. Prohibits the sale, delivery, or transfer of a handgun from a licensed importer, manufacturer, or dealer to an unlicensed individual unless the documentation of the transaction is sent to local law enforcement officers and the Federal Bureau of Investigation. - - - - - - - - - - 04/10/1986 H.Amdt.776 Amendment Passed in Committee of the Whole by Recorded Vote: 233 - 184 (Record Vote No: 72). 04/10/1986 H.Amdt.770 Amendment Passed (Amended) in Committee of the Whole by Recorded Vote: 286 - 136 (Record Vote No: 74). 04/09/1986 H.Amdt.775 Amendment Failed of Passage in Committee of Whole by Recorded Vote: 177 - 242 (Record Vote No: 71). 04/09/1986 H.Amdt.773 Amendment Failed of Passage in Committee of Whole by Recorded Vote: 176 - 248 (Record Vote No: 70). - - - - - - - - - - House Record Vote 74 was to amend the Senate bill. https://www.congress.gov/amendment/99th-congress/house-amendment/770 A substitute amendment to ease the interstate sale of both rifles and handguns. It eliminates the requirement that gun dealers notify police of handgun purchases and preempts state and local laws to ease interstate travel with handguns as well as rifles for any legal purpose. It also eliminates the need for many gun sellers to obtain a license and keep records of their gun sales. https://www.congress.gov/amendment/99th-congress/house-amendment/770/actions - - - - - - - - - - House Record vote 75 was to adopt the bill, as amended, including the Hughes Amendment. Record vote 75 (S.B. 49), adopted H.R. 4332, an amendment to the final bill. Action By: House of Representatives - - - - - - - - - -

Spot on. That's how it works. An additional wrinkle is that when the Supreme Court rules as a basis of existing law, including constitutional law, Congress might go ahead and pass new law that purports to change the law, or provides a guideline definition of terms that changes the constitutional meaning. The Supreme Court can, of course, find that the Congressional attempt is unavailing, because of the Constitution, or the Supreme Court can find that the Congressional effort, the new law, is constitutional, as written, and accept the legislature's redefinition of the bounds of the law. The same things is theoretically true with regulations as well, though I can't think of any examples.

Correct. The Supreme Court makes precedent by deciding cases. And the Supreme Court can overrule itself and previous precedent and establish NEW precedent, which stands until it overrules itself again, or until a constitutional amendment is ratified that overrules a Supreme Court position, or a statute is past that has the effect of overruling a Supreme Court precedent, and the Supreme Court acquiesces to the new statute. Precedent is always changeable by the authority that issued it. There is not one single aspect of US law or the Constitution that cannot be changed, amended, altered, with time, following the proper procedures. Supreme Court precedent is changed by later Supreme Court rulings. That's how the system works. NOTHING in the world of law is absolute, fixed and permanent. Law is made by man, and man can always change every single aspect of it, without any exceptions whatsoever, if enough men want to change it, and are able to sufficiently organize themselves to do so. That change might not be legal within the existing system. A SYSTEM may have sacrosanct laws that cannot be changed, in which case men determined to change it have to overthrow the system itself, in a revolution. And they do, from time to time. But the American Constitution contains within itself the means by which it can be amended, and there is nothing in it off limits to amendment. Some things are harder to amend than others, but NOTHING is off limits.

Exactly. Well put.

Does it matter whether the judge is a Catholic, Protestant, Jew, Muslim, or athiest? Or does the U.S. justice system recognize the common law right of self-defense? I would say, in truth, that the US justice system does not fully incorporate the Common Law of England as far as the right to keep and bear arms and self-defense goes. Rather, I'd say that a common law of America, which has come to differ substantially from old England, has developed over time, and that beyond that, American judges are all politicians, and live within a political and cultural climate that inflects their own beliefs, and sense of limitation, when it comes to the matter of guns and gun rights. In England, the restriction of guns came easily, because an iron-clad top- down legalism rules the road there. In America, it's not so easy because the people are neither as obedient nor as malleable as the English. And the judges come from the people and share those animal spirits. So while I would not dispute that American judges do indeed cite to the chains of laws going back, and conduct chains of reason that purport to simply be logical and inevitable extensions of the common law of jolly old England, in truth, their programming and prejudices make the result a sui generis common law of America, which is very distinctive on certain things, particularly matters of black-white race relations and guns.