U.S. Constitution

See other U.S. Constitution Articles

Title: You have NO IDEA what’s coming: Virginia Dems to unleash martial law attack on 2A counties using roadblocks to confiscate firearms and spark a shooting war

Source:

Government Slaves/Natural News

URL Source: https://governmentslaves.news/2019/ ... arms-and-spark-a-shooting-war/

Published: Dec 19, 2019

Author: Mike Adams

Post Date: 2019-12-21 11:10:14 by Deckard

Keywords: None

Views: 44265

Comments: 171

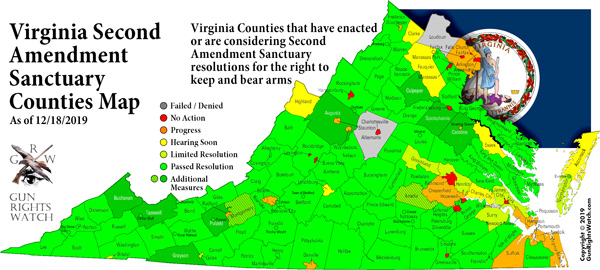

After passing extremely restrictive anti-gun legislation in early 2020, Virginia has a plan to deploy roadblocks at both the county and state levels to confiscate firearms from law-abiding citizens (at gunpoint, of course) as part of a deliberate effort to spark a shooting war with citizens, sources are now telling Natural News. Some might choose to dismiss such claims as speculation, but these sources now say that Virginia has been chosen as the deliberate flashpoint to ignite the civil war that’s being engineered by globalists. Their end game is to unleash a sufficient amount of violence to call for UN occupation of America and the overthrow of President Trump and the republic. Such action will, of course, also result in the attempted nationwide confiscation of all firearms from private citizens, since all gun owners will be labeled “domestic terrorists” if they resist. Such language is already being used by Democrat legislators in the state of Virginia. The Democrat-run impeachment of President Trump is a necessary component for this plan, since the scheme requires Trump supporters to be painted as “enraged domestic terrorists” who are seeking revenge for the impeachment. This is how the media will spin the stories when armed Virginians stand their ground and refuse to have their legal firearms confiscated by police state goons running Fourth Amendment violating roadblocks on Virginia roads. Roadblocks will be set up in two types of locations, sources tell Natural News: 1) On roads entering the state of Virginia from neighboring states that have very high gun ownership, such as Kentucky, Tennessee and North Carolina, and 2) Main roads (highways and interstates) that enter the pro-2A counties which have declared themselves to be Second Amendment sanctuaries. With over 90 counties now recognizing some sort of pro-2A sanctuary status, virtually the entire State of Virginia will be considered “enemy territory” by the tyrants in Richmond who are trying to pull off this insidious scheme. As the map shows below, every green county has passed a pro-2A resolution of one kind or another. As you can see, nearly the entire state is pro-2A, completely surrounding the Democrat tyrants who run the capitol of Richmond. The purpose of the roadblocks, to repeat, has nothing to do with public safety or enforcing any law. It’s all being set up to spark a violent uprising against the Virginia Democrats and whatever law enforcement goons are willing to go along with their unconstitutional demands to violate the fundamental civil rights of Virginian citizens. Over 90 Virginian counties, cities and municipalities have so far declared themselves to be pro-2A regions, meaning they will not comply with the gun confiscation tyranny of Gov. Northam and his Democrat lackeys. Democrats in Virginia have threatened to activate the National Guard to attack pro-2A “terrorists,” and a recent statement from the Guard unit in Virginia confirms that the Guard has no intention to resist Gov. Northam’s outrageous orders, even if they are illegal or unconstitutional. One county in Virginia — Tazewell — has already activated its own militia in response. As reported by FirearmsNews.com: In addition to passing their Second Amendment Sanctuary Resolution, the county also passed a Militia Resolution. This resolution formalizes the creation, and maintenance of a defacto civilian militia in the county of Tazewell. And to get a better understanding why the council members passed this resolution, Firearms News reached out to one of its members, Thomas Lester. Mr. Lester is a member of the council, as well as a professor of American History and Political Science. Firearms News: Councilman Lester, what are the reasons behind passing this new resolution, and what does it mean for the people of Tazewell County? Tom Lester: … the purpose of the militia is not just to protect the county from domestic danger, but also protect the county from any sort of tyrannical actions from the Federal government. Our constitution is designed to allow them to use an armed militia as needed. If the (Federal) government takes those arms away, it prevents the county from fulfilling their constitutional duties. The situation is escalating rapidly in Virginia, which is precisely what Democrats and globalists are seeking. As All News Pipeline reports: With many Virginia citizens angry with the threat of tyranny exploding there, ANP was recently forwarded an email written by a very concerned Virginia citizen who warned that Democratic leadership is pushing Virginia there towards another ‘shot heard around the world’ with Virginia absolutely the satanic globalists new testing ground for disarming all of America in a similar fashion should they be successful there. And while we’ll continue to pray for peace in America, it’s long been argued that it’s better to go down fighting than to be a slave to tyranny for the rest of one’s life. And with gun registration seemingly always preceding disarmament and disarmament historically leading to genocide, everybody’s eyes should be on what’s happening now in Virginia. With the mainstream media clearly the enemy of the American people and now President Trump confirming they are ‘partners in crime’ with the ‘deep state’ that has been attempting an illegal coup upon President Trump ever since he got into office, how can outlets such as CNN, MSNBC, the NY Times, Washington Post and all of the others continuously pushing the globalists satanic propaganda be held accountable and responsible for the outright madness they are unleashing upon America? Where is all this really headed? The bottom line goal of the enemies of America is to transform the country into a UN-occupied war zone, where UN troops go door to door, confiscating weapons from the American people. President Trump will be declared an “illegitimate dictator” and accused of war crimes, since Democrats and the media have already proven they can dream up any crime imaginable and accuse the President of that crime, without any basis in fact. And as we know with the Dems, if they can’t rule America, they will seek to destroy it. Causing total chaos is their next best option to resisting Trump’s efforts to drain the swamp, since the Dems know they can’t defeat Trump in an honest election. Expect Virginia to be the ignition point for all this. Even the undercover cops who work there are now warning about what’s coming. Via WesternJournal.com: Virginia’s Democratic politicians appear to be ready to drive the state into a period of massive civil unrest with no regard for citizens’ wishes, but conservatives in the commonwealth will not be stripped of their rights without a fight. In the face of expected wide-reaching bans on so-called assault weapons, high-capacity magazines, and other arms protected under the 2nd Amendment, Virginians are standing up to Democratic tyranny. A major in the Marine Corps reserves took an opportunity during a Dec. 3 meeting to warn the Board of Supervisors of Fairfax County about trouble on the horizon. Ben Joseph Woods spoke about his time in the military, his federal law enforcement career and his fears about where politicians are taking Virginia. “I work plainclothes law enforcement,” Woods said. “I walk around without a uniform, people don’t see my badge, people don’t see my gun, and I can tell you: People are angry.” Woods said that the situation in Virginia is becoming so dangerous that he is close to moving his own wife and unborn child out of the state. The reason is because my fellow law enforcement officers I’ve heard on more than one occasion tell me they would not enforce these bills regardless of whether they believe in them ideologically,” Woods said, “because they believe that there are so many people angry — in gun shops, gun shows, at bars we’ve heard it now — people talking about tarring and feathering politicians in a less-than-joking manner.” As Woods mentioned politicians themselves could very well be in danger because of their decisions, several rebel yells broke out as the crowd cheered him on. Stay informed. Things are about to happen over the next 10 months that you would have never imagined just five years ago. And to all those who mocked our warnings about the coming civil war, you are about to find yourself in one. Sure hope you know how to run an AR platform and build a water filter. Things won’t go well for the unprepared, especially in the cities. And, by the way, Richmond is surrounded by patriots. At what point will the citizens of Virginia decide to arrest and incarcerate all the lawless, treasonous tyrants in Richmond who tried to pull this stunt? I have a feeling there’s about to be a real shortage of rope across Virginia…

The gun confiscation roadblocks are almost sure to start a shooting war

The enemies of America want to turn the entire country into a UN-occupied war zone and declare President Trump to be an “illegitimate dictator”

Post Comment Private Reply Ignore Thread

Top • Page Up • Full Thread • Page Down • Bottom/Latest

Comments (1-117) not displayed.

.

.

.

#118. To: misterwhite (#114)

You said all manner of ridiculous shit. So what? The Firearms Owners Protection Act (FOPA) was passed by the Senate on May 19, 1986. The Bill that passed into law was the Senate bill, S.49. No part of the FOPA passed into law other than as part of Senate Bill 49 which was passed on May 19, 1986. The Hughes Amendment passed in Committee in the House by a voice vote as an amendment to an amendment to an amendment to the Volkmer Amendment which was in the nature of a substitute for the text of the Hughes-Rodino Bill in the House. Who gives a flying shit about a committee vote in the House? By voice vote in Committee, ruled the Ayes had it, the Hughes Amendment became part of the text of the Volkmer Amendment which was in the nature of a substitute for the text of the Hughes-Rodino Bill in the House. The House Hughes-Rodino Bill, H.R.4332, before or after the Hughes amendment to the amendment to the amendment to the Volkmer Amendment in the nature of a substitute, was never adopted as law. In April 10, 1986, the House incorporated HR. 4332 into Senate bill S.49 as an amendment. The Senate Bill, S.49 became the law known as the Firearms Owners' Protection Act of 1986. On May 19, 1986, the Senate voted its approval of S.49, as amended, and President Reagan signed it into law the same day. S.49 - Firearms Owners' Protection Act 99th Congress (1985-1986) If it's not a law, stop bitching and just go out and buy yourself a brand new machine gun.

Heller at 626: Heller at 627-28: Black's Law Dictionary, 6 Ed. The "right to keep and bear arms" existed in the colonies, was brought forth into the states before the union, and was protected by the 2nd Amendment. The right which existed in the colonies came from the English common law. The Framers saw no need to explain to themselves what that right to keep and bear arms was. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/blackstone_bk1ch1.asp Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England Book the First - Chapter the First: Of the Absolute Rights of Individuals Heller at 593-95: And, of course, what the Stuarts had tried to do to their political enemies, George III had tried to do to the colonists. In the tumultuous decades of the 1760’s and 1770’s, the Crown began to disarm the inhabitants of the most rebellious areas. That provoked polemical reactions by Americans invoking their rights as Englishmen to keep arms. A New York article of April 1769 said that “[i]t is a natural right which the people have reserved to themselves, confirmed by the Bill of Rights, to keep arms for their own defence.” A Journal of the Times: Mar. 17, New York Journal, Supp. 1, Apr. 13, 1769, in Boston Under Military Rule 79 (O. Dickerson ed. 1936); see also, e.g., Shippen, Boston Gazette, Jan. 30, 1769, in 1 The Writings of Samuel Adams 299 (H. Cushing ed. 1968). They understood the right to enable individuals to defend themselves. As the most important early American edition of Blackstone’s Commentaries (by the law professor and former Antifederalist St. George Tucker) made clear in the notes to the description of the arms right, Americans understood the “right of self-preservation” as permitting a citizen to “repe[l] force by force” when “the intervention of society in his behalf, may be too late to prevent an injury.” 1 Blackstone’s Commentaries 145–146, n. 42 (1803) (hereinafter Tucker’s Blackstone). See also W. Duer, Outlines of the Constitutional Jurisprudence of the United States 31–32 (1833). There seems to us no doubt, on the basis of both text and history, that the Second Amendment conferred an individual right to keep and bear arms. Of course the right was not unlimited, just as the First Amendment’s right of free speech was not, see, e.g., United States v. Williams, 553 U. S. ___ (2008). Thus, we do not read the Second Amendment to protect the right of citizens to carry arms for any sort of confrontation, just as we do not read the First Amendment to protect the right of citizens to speak for any purpose. Before turning to limitations upon the individual right, however, we must determine whether the prefatory clause of the Second Amendment comports with our interpretation of the operative clause. Heller at 626-28: We also recognize another important limitation on the right to keep and carry arms. Miller said, as we have explained, that the sorts of weapons protected were those “in common use at the time.” 307 U. S., at 179. We think that limitation is fairly supported by the historical tradition of prohibiting the carrying of “dangerous and unusual weapons.” See 4 Blackstone 148–149 (1769); 3 B. Wilson, Works of the Honourable James Wilson 79 (1804); J. Dunlap, The New-York Justice 8 (1815); C. Humphreys, A Compendium of the Common Law in Force in Kentucky 482 (1822); 1 W. Russell, A Treatise on Crimes and Indictable Misdemeanors 271–272 (1831); H. Stephen, Summary of the Criminal Law 48 (1840); E. Lewis, An Abridgment of the Criminal Law of the United States 64 (1847); F. Wharton, A Treatise on the Criminal Law of the United States 726 (1852). See also State v. Langford, 10 N. C. 381, 383–384 (1824); O’Neill v. State, 16 Ala. 65, 67 (1849); English v. State, 35 Tex. 473, 476 (1871); State v. Lanier, 71 N. C. 288, 289 (1874). It may be objected that if weapons that are most useful in military service—M–16 rifles and the like—may be banned, then the Second Amendment right is completely detached from the prefatory clause. But as we have said, the conception of the militia at the time of the Second Amendment’s ratification was the body of all citizens capable of military service, who would bring the sorts of lawful weapons that they possessed at home to militia duty. It may well be true today that a militia, to be as effective as militias in the 18th century, would require sophisticated arms that are highly unusual in society at large. Indeed, it may be true that no amount of small arms could be useful against modern-day bombers and tanks. But the fact that modern developments have limited the degree of fit between the prefatory clause and the protected right cannot change our interpretation of the right.

They NEVER limited the use of those weapons to "militia purposes". Just the opposite. They expected militia members to bring the same weapons used for "non-militia purposes". misterwhite, victim of dictum. Heller at 625:

Heller at 625:

I'm mailing him a sympathy card as I type this.

Finally. Thank you.

There have never been any federal laws against concealed carry, so there were never any Second Amendment challenges. States have always been free to regulate firearms under their respective state constitutions. "Indeed, it may be true that no amount of small arms could be useful against modern- day bombers and tanks." Which is why the second amendment protects ALL arms -- including bombers and tanks -- suitable for use by a state militia. The second amendment was written to protect state militias from federal infringement. Individual arms for personal use were protected by state constitutions. Who in their right mind would look to the federal government to protect such an important right?

I would hope not. Yes, it's true that United States v. Miller was mentioned in Footnote #8 in Lewis v. United States -- a 1980 case involving a firearm possessed by a felon. Why would the Heller court even mention this case, much less consider it? Probably because if they looked at the Miller case directly -- not footnoted dictum -- they would see that the Second Amendment guarantees no right to keep and bear a firearm that does not have ‘some reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia’.

Finally. Thank you. You're welcome. To avoid your future confusion, the Hughes Amendment passed in Committee as an amendment to an amendment to an amendent to the Volkmer Amendment in the nature of a replacement text to the text of H.R. 4332, the Hughes-Rodino Bill. However, H.R. 4332 was not signed into law. Senate Bill S.49 was signed into law. Just to be clear.

The Framers of the Second Amendment. There were loads of State laws prohibiting concealed carry, as early as an 1820 Kentucky concealed carry law that was the subject of litigation in Bliss v. Commonwealth. 12 Littell 90 Ky. 1822 This was an indictment founded on the act of the legislature of this state, "to prevent persons in this commonwealth from wearing concealed arms." The act provides, that any person in this commonwealth, who shall hereafter wear a pocket pistol, dirk, large knife, or sword in a cane, concealed as a weapon, unless when travelling on a journey, shall be fined in any sum not less than one hundred dollars; which may be recovered in any court having jurisdiction of like sums, by action of debt, or on presentment of a grand jury. The indictment, in the words of the act, charges Bliss with having worn concealed as a weapon, a sword in a cane. Bliss was found guilty of the charge, and a fine of one hundred dollars assessed by the jury, and judgment was thereon rendered by the court. To reverse that judgment, Bliss appealed to this court. In argument the judgment was assailed by the counsel of Bliss, exclusively on the ground of the act, on which the indictment is founded, being in conflict with the twenty third section of the tenth article of the constitution of this state. That section provides, "that the right of the citizens to bear arms in defence of themselves and the state, shall not be questioned." The provision contained in this section, perhaps, is as well calculated to secure to the citizens the right to bear arms in defence of themselves and the state, as any that could have been adopted by the makers of the constitution. If the right be assailed, immaterial through what medium, whether by an act of the legislature or in any other form, it is equally opposed to the comprehensive import of the section. The legislature is no where expressly mentioned in the section; but the language employed is general, without containing any expression restricting its import to any particular department of government; and in the twenty eighth section of the same article of the constitution, it is expressly declared, "that every thing in that article is excepted out of the general powers of government, and shall forever remain inviolate; and that all laws contrary thereto, or contrary to the constitution, shall be void." It was not, however, contended by the attorney for the commonwealth, that it would be competent for the legislature, by the enactment of any law, to prevent the citizens from bearing arms either in defence of themselves or the state; but a distinction was taken between a law prohibiting the exercise of the right, and a law merely regulating the manner of exercising that right; and whilst the former was admitted to be incompatible with the constitution, it was insisted, that the latter is not so, and under that distinction, and by assigning the act in question a place in the latter description of laws, its consistency with the constitution was attempted to be maintained. 3. That the provisions of the act in question do not import an entire destruction of the right of the citizens to bear arms in defence of themselves and the state, will not be controverted by the court; for though the citizens are forbid wearing weapons concealed in the manner described in the act, they may, nevertheless, bear arms in any other admissible form. But to be in conflict with the constitution, it is not essential that the act should contain a prohibition against bearing arms in every possible form--it is the right to bear arms in defence of the citizens and the state, that is secured by the constitution, and whatever restrains the full and complete exercise of that right, though not an entire destruction of it, is forbidden by the explicit language of the constitution. If, therefore, the act in question imposes any restraint on the right, immaterial what appellation may be given to the act, whether it be an act regulating the manner of bearing arms or any other, the consequence, in reference to the constitution, is precisely the same, and its collision with that instrument equally obvious. And can there be entertained a reasonable doubt but the provisions of the act import a restraint on the right of the citizens to bear arms? The court apprehends not. The right existed at the adoption of the constitution; it had then no limits short of the moral power of the citizens to exercise it, and it in fact consisted in nothing else but in the liberty of the citizens to bear arms. Diminish that liberty, therefore, and you necessarily restrain the right; and [Volume 5, Page 213] such is the diminution and restraint, which the act in question most indisputably imports, by prohibiting the citizens wearing weapons in a manner which was lawful to wear them when the constitution was adopted. In truth, the right of the citizens to bear arms, has been as directly assailed by the provisions of the act, as though they were forbid carrying guns on their shoulders, swords in scabbards, or when in conflict with an enemy, were not allowed the use of bayonets; and if the act be consistent with the constitution, it cannot be incompatible with that instrument for the legislature, by successive enactments, to entirely cut off the exercise of the right of the citizens to bear arms. For, in principle, there is no difference between a law prohibiting the wearing concealed arms, and a law forbidding the wearing such as are exposed; and if the former be unconstitutional, the latter must be so likewise. We may possibly be told, that though a law of either description, may be enacted consistently with the constitution, it would be incompatible with that instrument to enact laws of both descriptions. But if either, when alone, be consistent with the constitution, which, it may be asked, would be incompatible with that instrument, if both were enacted? The law first enacted would not be; for, as the argument supposes either may be enacted consistent with the constitution, that which is first enacted must, at the time of enactment, be consistent with the constitution; and if then consistent, it cannot become otherwise, by any subsequent act of the legislature. It must, therefore, be the latter act, which the argument infers would be incompatible with the constitution. But suppose the order of enactment were reversed, and instead of being the first, that which was first, had been the last; the argument, to be consistent, should, nevertheless, insist on the last enactment being in conflict with the constitution. So, that the absurd consequence would thence follow, of making the same act of the legislature, either consistent with the constitution, or not so, according as it may precede or follow some other enactment of a different import. Besides, by insisting on the previous act producing any effect on the latter, the argument implies that the previous one operates as a partial restraint on the right of the citizens to bear arms, and proceeds on the notion, that by prohibiting the exercise of the residue of right, not affected by the first act, the latter act comes in collision with the constitution. But it should not be forgotten, that it is not only a part of the right that is secured by the constitution; it is the right entire and complete, as it existed at the adoption of the constitution; and if any portion of that right be impaired, immaterial how small the part may be, and immaterial the order of time at which it be done, it is equally forbidden by the constitution. 4. Hence, we infer, that the act upon which the indictment against Bliss is founded, is in conflict with the constitution; and if so, the result is obvious—the result is what the constitution has declared it shall be, that the act is void. And if to be incompatible with the constitution makes void the act, we must have been correct, throughout the examination of this case, in treating the question of compatibility, as one proper to be decided by the court. For it is emphatically the duty of the court to decide what the law is; and how is the law to be decided, unless it be known and how can it be known without ascertaining, from a comparison with the constitution, whether there exist such an incompatibility between the acts of the legislature and the constitution, as to make void the acts? A blind enforcement of every act of the legislature, might relieve the court from the trouble and responsibility of deciding on the consistency of the legislative acts with the constitution; but the court would not be thereby released from its obligations to obey the mandates of the constitution, and maintain the paramount authority of that instrument; and those obligations must cease to be acknowledged, or the court become insensible to the impressions of moral sentiment, before the provisions of any act of the legislature, which in the opinion of the court, conflict with the constitution, can be enforced. Whether or not an act of the legislature conflicts with the constitution, is, at all times, a question of great delicacy, and deserves the most mature and deliberate consideration of the court. But though a question of delicacy, yet as it is a judicial one, the court would be unworthy its station, were it to shrink from deciding it, whenever in the course of judicial examination, a decision becomes material to the right in contest. The court should never, on slight implication or vague conjecture, pronounce the legislature to have transcended its authority in the enactment of law; but when a clear and strong conviction is entertained, that an act of the legislature is incompatible with the constitution, there is no alternative for the court to pursue, but to declare that conviction, and pronounce the act inoperative and void. And such is the conviction entertained by a majority of the court, (Judge Mills dissenting,) in relation to the act in question. Note well that it is the duty of the judicial branch to decide whether a law is constitutional when such decision become material to the rught in contest. Now, before you get all warm and fuzzy about that law being overturned as repugnant to the Kentucky constitution, the People of the Great State of Kentucky saw fit to amend their constitution and in 1850 the Kentucky constitution Bill of Rights provided: Ain't that an aw shit moment.

Why would the Heller court even mention this case, much less consider it? Probably because if they looked at the Miller case directly -- not footnoted dictum -- they would see that the Second Amendment guarantees no right to keep and bear a firearm that does not have ‘some reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia’. Lewis in 1980 quoted from Miller. Lewis was fully argued before SCOTUS. At 445 U.S. 56: Andrew J. Levander argued the cause pro hac vice for the United States. With him on the brief were Solicitor General McCree, Assistant Attorney General Heymann, Deputy Solicitor General Frey, Jerome M. Feit, and Joel M. Gershowitz It was Miller that was not fully argued before the Supreme Court. A dictum from Miller is no less a dictum because it is described as such by the Supreme Court in a footnote of a subsequent opinion. While the appearance of attorneys and argument for both sides in Lewis is clearly documented, in Miller it is clearly documented that there was "No appearance for appellees." 307 U.S. 175 As we also know, Miller's corpse did not appear for argument or the reading of the Opinion. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Clayton E. Cramer, For the Defense of Themselves and the State, The Original Intent and Judicial Interpretation of the Right to Keep and Bear Arms, Praeger Publishers, 1994, page 189: The Court did not say that a short-barreled shotgun was unprotected—just that no evidence had been presented to demonstrate such a weapon was "any part of the ordinary military equipment" or that it could "contribute to the common defense." - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Brian L. Frye, The Peculiar Story of United States v. Miller, NYU Journal of Law and Liberty, Vol 3:48 at 50: At 57: Gutensohn was attorney for Miller. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Heller at 626-28: We also recognize another important limitation on the right to keep and carry arms. Miller said, as we have explained, that the sorts of weapons protected were those “in common use at the time.” 307 U. S., at 179. We think that limitation is fairly supported by the historical tradition of prohibiting the carrying of “dangerous and unusual weapons.” See 4 Blackstone 148–149 (1769); 3 B. Wilson, Works of the Honourable James Wilson 79 (1804); J. Dunlap, The New-York Justice 8 (1815); C. Humphreys, A Compendium of the Common Law in Force in Kentucky 482 (1822); 1 W. Russell, A Treatise on Crimes and Indictable Misdemeanors 271–272 (1831); H. Stephen, Summary of the Criminal Law 48 (1840); E. Lewis, An Abridgment of the Criminal Law of the United States 64 (1847); F. Wharton, A Treatise on the Criminal Law of the United States 726 (1852). See also State v. Langford, 10 N. C. 381, 383–384 (1824); O’Neill v. State, 16 Ala. 65, 67 (1849); English v. State, 35 Tex. 473, 476 (1871); State v. Lanier, 71 N. C. 288, 289 (1874). It may be objected that if weapons that are most useful in military service—M–16 rifles and the like—may be banned, then the Second Amendment right is completely detached from the prefatory clause. But as we have said, the conception of the militia at the time of the Second Amendment’s ratification was the body of all citizens capable of military service, who would bring the sorts of lawful weapons that they possessed at home to militia duty. It may well be true today that a militia, to be as effective as militias in the 18th century, would require sophisticated arms that are highly unusual in society at large. Indeed, it may be true that no amount of small arms could be useful against modern-day bombers and tanks. But the fact that modern developments have limited the degree of fit between the prefatory clause and the protected right cannot change our interpretation of the right.

The Miller court held they cannot take judicial notice that a shotgun having a barrel less than 18 inches long has today any reasonable relation to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia, and therefore could not say that the Second Amendment guarantees to the citizen the right to keep and bear such a weapon. And they reversed a lower court decision that said it did. Hardly dictum.

Correct. So what are we to deduce from that statement by the U.S. Supreme Court?

And they reversed a lower court decision that said it did. Hardly dictum. You are full of crap and don't know what you are talking about. Quote your imaginary holding from Miller, do not provide your nonsense variation of the dictum therein and call it a holding. The Opinion of the Court in Miller begins at 307 U.S. 175, and the relevant paragraph is in Miller at page 307 U.S. 178, second paragraph. Try reading Miller and the case cited therein, Aymette. Digest the holding in Aymette which is cited as authority by Miller.

Correct. So what are we to deduce from that statement by the U.S. Supreme Court? We are to deduce that Miller filed a demurrer, filed no brief, and made no appearance in the court, personally or through attorney. A demurrer is an assertion, made without disputing the facts, that the opponent's pleading is insufficient as a matter of law. We are to deduce that the Court, in the absolute and complete absence of any evidence presented which could even tend to show that the weapon had any reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia, could not make believe there was such evidence. The Court did not find that such evidence did not exist, just that none had been presented. Lacking evidence upon which to form an opinion, the Court went on to relate the matter upon which it could not form an opinion. Because no relevant evidence whatever had been presented, the Court could not say that the weapon was any part of the ordinary military equipment or that its use could contribute to the common defense. That is what the Court could not say, due to a complete absence of evidence. The Court then cited as authority, Aymette v State, 2 Humphrey's (Tenn.) 154, 158.

The Miller court held: 2. (The National Firearms Act) Not violative of the Second Amendment of the Federal Constitution. P. 178. AND The Court cannot take judicial notice that a shotgun having a barrel less than 18 inches long has today any reasonable relation to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia, and therefore cannot say that the Second Amendment guarantees to the citizen the right to keep and bear such a weapon. MEANING that if a weapon has today any reasonable relation to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia, the Second Amendment DOES guarantee to the citizen the right to keep and bear such a weapon.

Ah. So their decision was to be based on whether or not the weapon had any reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia. I agree and that's the only point I was making. Because Heller ignored that important point.

Ah. So their decision was to be based on whether or not the weapon had any reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia. You evidently have a reading comprehension problem. If the weapon had not relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia, 2A did not apply. If the weapon did have some relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia, then the court had to consider if it was protected by 2A. The court overruled an unexplained grant of a demurrer and remanded the case to the District Court. Further proceedings did not occur because Miller disappeared.

The Miller court held: 2. (The National Firearms Act) Not violative of the Second Amendment of the Federal Constitution. P. 178. AND The Court cannot take judicial notice that a shotgun having a barrel less than 18 inches long has today any reasonable relation to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia, and therefore cannot say that the Second Amendment guarantees to the citizen the right to keep and bear such a weapon. THAT is not even part of the Opinion in Miller. It is from page 307 U.S. 174. In my #131 I led you by the nose to the precise page and paragraph of the Opinion of the Court to which you are obviously very reluctant to quote, rather preferring to misrepresent and misread the court reporter's syllabus. Why are you unable or unwilling to quote the actual Opinion of the Court? You also have amply demonstrated that you are legally incompetent to read and understand the Syllabus written by the court reporter. In the Syllabus, TWO holdings are identified, and they are numbered 1 and 2. APPEAL FROM THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF ARKANSAS. No. 696. Argued March 30, 1939.-Decided May 15, 1939. The National Firearms Act, as applied to one indicted for transporting in interstate commerce a 12-gauge shotgun with a barrel less than 18 inches long, without having registered it and without having in his possession a stamp-affixed written order for it, as required by the Act, held: 1. Not unconstitutional as an invasion of the reserved powers of the States. Citing Sonzinsky v. United States, 300 U. S. 506, and Narcotic Act cases. P. 177. 2. Not violative of the Second Amendment of the Federal Constitution. P. 178. The Court can not take judicial notice that a shotgun having a barrel less than 18 inches long has today any reasonable relation to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia; and therefore can not say that the Second Amendment guarantees to the citizen the right to keep and bear such a weapon. 26 F. Supp. 1002, reversed. APPEAL under the Criminal Appeals Act from a judgment sustaining a demurrer to an indictment for violation of the National Firearms Act. Mr. Gordon Dean argued the cause, and Solicitor General Jackson, Assistant Attorney General McMahon, and Messrs. William W. Barron, Fred E. Strine, George F. Kneip, W. Marvin Smith, and Clinton R. Barry were on a brief, for the United States. No appearance for appellees. MR. JUSTICE MCREYNOLDS delivered the opinion of the Court. The two numbered paragraphs, with page citations to the Opinion of the Court, are the court reporter's statement of holdings. The unnumbered paragraph, here highlighted in blue, with no page citation, is not holding. The Opinion of the Court at page 178 reads:

Miller Opinion, New York Times, Tuesday, May 16, 1939, page 15: The decision did not solve any problems; criminals use sawed-off shotguns as readily today as they did fifty years ago. It alluded to, but did not define, the Second Amendment: does "well regulated" mean well governed or well trained? Who constitutes "the militia"? How does "the right of the people" in the Second Amendment differ from the "right of the people" in the First, Fourth, or any other? And if does differ, why? McReynolds' approach reflects the elitist disdain the modern federal judiciary has shown for the Second Amendment, which they consider "obsolete" or "dead" — ignore it to the degree possible, gloss over any inconsistencies when necessary, then dismiss it with a wave of the hand. They wish it would go away. The questions posed by the Second Amendment, are, like firearms, abhorrent and of interest only to dullards, the lower classes, and criminals. We can only wonder what McReynolds would have written if a sawed-off shotgun had been used by an irate small businessman, protecting his meager gold stash from seizure by New Deal agents. The true importance of the case lies in its basis for reference by the Supreme Court when the Second Amendment is finally argued directly of and for itself. Using the judicial protocol of stare decisis, the policy of standing by precedents and not disturbing "settled" points, the justices may utilize Miller, ambiguous as it is on the subject, as "proof" that the Second Amendment is a collective guarantee rather than an individual right. The idea, it might be argued, is that "consistency" of law, formed by basing current decisions on the foundations of prior decisions - - even questionable ones - - is more important than truth. Another consideration regarding the case is that the appellees, Miller and Layton, were not even represented. Miller, in fact, had been murdered before the case was argued. The assault the government made against an individual's right to bear arms went without rebuttal, beyond Gutensohn's poorly written demurrer to the indictment. This will not be the circumstance in the inevitable future decision. Even with the Second Amendment defenseless against attack, McReynolds, as noted, refused to bring forth a blanket decision covering all firearms. Nor did he actively dispute the people's right to bear arms as individuals, perhaps realizing he would be on uncertain ground after reading militia laws which dictated that the members, the "body of the people", supply their own arms. The result was a weak swat at the "gangster" element of the time: "In the absence of any evidence tending to show that possession or use of a 'shotgun having a barrel of less than eighteen inches in length' at this time has some reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia, we cannot say that the Second Amendment guarantees the right to keep and bear such an instrument. Certainly it is not within judicial notice that this weapon is any part of the ordinary military equipment or that its use could contribute to the common defense." This conclusion is debatable, as thirty thousand short-barrel shotguns were purchased by the U.S. government for the armed forces in World War I. 1 His inference about "the common defense" is also faulty, as shall be shown. The historical sources used for the decision are of interest, but even more important are the sources not consulted. For example, McReynolds refers us to a chapter on the role of the militia in Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations, which was not even published until 1776 and can hardly be considered a reference manual for the Founding Fathers. The opinion and the appellant's self-contradictory brief continually point us to English common law, and prior decisions based on English common law, and even colonial militia laws that plainly direct that the people must provide their own arms. But no one bothered to consider the words of the very men who demanded the Bill of Rights of which the Second Amendment is a part! This is nothing short of incredible. Jefferson, Madison, Mason, and a host of other Founding Fathers were obvious in their feelings on the subject. Noting the militia clauses of the Constitution, McReynolds writes the following in his opinion: "With obvious purpose to assure the continuation and render possible the effectiveness of such forces the declaration and guarantee of the Second Amendment were made. It must be interpreted and applied with that end in view." With "obvious purpose"? The Second Amendment specifies the guarantee of an individual right, and a brief review of the evolution of the Second Amendment in America establishes this. The duty of militia service is a natural result of that right, particularly in a republic fearful of standing armies, but it is inane to say the duty supersedes the right on which it is predicated. As it applies to the Bill of Rights, the thought that later led to the Second Amendment was first found as article 13 of the Virginia Declaration of Rights, written by George Mason in 1776. As noted in The Roots of the Bill of Rights, "Of the 16 articles in the Virginia Declaration, nine state fundamental general principals of a free republic (of these perhaps the most consequential was the statement in Article 5 of the separation of powers as a rule of positive law--apparently the first such statement in an organic instrument). The remaining seven articles safeguard specific individual rights." 2 As a proof that the right is individual, not collective, consider the evolution of article 13. When approved on June 29, 1776, it read: 13. That a well regulated militia, composed of the body of the people, trained to arms, is the proper, natural, and safe defence of a free State; that standing armies in time of peace should be avoided, as dangerous to liberty; and that in all cases, the military should be under strict subordinance to, and governed by, the civil power. Pennsylvania statesmen, using the Virginia Declaration as a guide, passed The Pennsylvania Declaration of Rights on September 28, 1776. Their Article XIII was even more specific regarding the individual's right to bear arms: XIII. That the people have a right to bear arms for the defence of themselves and the state; and as standing armies in the time of peace are dangerous to liberty, they ought not to be kept up; And that the military should be kept under strict subordination to, and governed by, the civil power. In the intervening years between 1776 and 1787, independence was won and a proposed national constitution drafted. Upon presentation to the states for ratification, debate arose between the factions favoring the Constitution as presented (the Federalists) and those who either opposed ratification or who demanded a Bill of Rights as a guarantee of their individual liberties (the Antifederalists). In Pennsylvania, the Federalist majority was able to ratify the Constitution, but not without considerable dissent from the Antifederalists. To bring forth their argument to the public, the dissenters published their reasons for disagreement. From "The Address and Reasons of Dissent of the Minority of the Convention of the State of Pennsylvania to their Constituents, 1787," we find the following: " . . . Thus situated we entered on the examination of the proposed system of government, and found it to be such as we could not adopt, without, as we conceived, surrendering up your dearest rights. We offered our objections to the convention, and opposed those parts of the plan, which, in our opinion, would be injurious to you, in the best manner we were able; and closed our arguments by offering the following propositions to the convention . . ." Of their propositions, the seventh clearly addressed the right to keep and bear arms as an individual right. 7. That the people have a right to bear arms for the defence of themselves and their own State or the United States, or for the purpose of killing game; and no law shall be passed for disarming the people or any of them unless for crimes committed, or real danger of public injury from individuals; and as standing armies in the time of peace are dangerous to liberty, they ought not to be kept up; and that the military shall be kept under strict subordination to, and be governed by the civil powers. The importance of the amendments proposed by the Pennsylvania Convention minority is that they were used as a model for other states, including Virginia, which desired ratification, yet also wanted a Bill of Rights. Virginia, with its wealth, population, and position of leadership in the Revolutionary period, stood as the pivotal state if the Constitution was to be adopted. Virginia's proposed federal Bill of Rights is momentous in that it represented the first specification of the document. Congress listened; every guarantee proposed by Virginia, except one, later found a place in the federal Bill of Rights. From the Virginia ratification document of June 27, 1788 comes the following affirmation that the right to bear arms should be an individual right: "That there be a declaration or bill of rights asserting, and securing from encroachment, the essential and unalienable rights of the people, in some such manner as the following: … 17th. That the people have a right to keep and bear arms; that a well-regulated militia, composed of the body of the people trained to arms, is the proper, natural, and safe defence of a free state; that standing armies, in time of peace, are dangerous to liberty, and therefore ought to be avoided, as far as the circumstances and protection of the community will admit; and that, in all cases, the military should be under strict subordination to, and governed by, the civil power." Note that article 17 is essentially the same as article 13 from the Virginia Declaration of Rights, except for one important distinction: the phrase "That the people have a right to keep and bear arms" now leads the section! As with the Pennsylvania minority report, the Virginia proposal is distinct in specifying this individual right, though more succinctly than the Pennsylvania model. The Virginia statesmen were thrifty with words, but it is absurd to think they added the clause for any reason other than to express exactly what it says. Otherwise, article 13 would have served the purpose unchanged. It is also notable that George Mason, who penned article 13, participated in the deliberations that produced article 17. One would think he would have objected forcefully if the boundaries of his intent had been violated. Far from it. It was during this convention Mr. Mason said "Mr. Chairman, a worthy member has asked who are the militia, if they be not the people of this country, and if we are not to be protected from the fate of the Germans, Prussian, & c., by our representation? I ask, Who are the militia? They consist now of the whole people, except a few public officers."3 Other states also amplified a more thorough meaning of their militia clauses upon ratification debate. New Hampshire, in their Bill of Rights dated 1783, noted in section XXIV that: "A well regulated militia is the proper, natural, and sure defense of a state." In their proposed amendments to the Constitution in 1788 they suggested: Twelfth, Congress shall never disarm any Citizen unless such as are or have been in Actual Rebellion. In New York, the Constitution of 1777 read: XL. And whereas it is of the utmost importance to the safety of every State that it should always be in a condition of defence; and it is the duty of every man who enjoys the protection of society to be prepared and willing to defend it; this convention therefore, in the name and by the authority of the good people of this State, doth ordain, determine, and declare that the militia of this State, at all times hereafter, as well in peace as in war, shall be armed and disciplined, and in readiness for service. At the 1788 New York Ratification Convention, Alexander Hamilton, the acknowledged leader of the Federalist movement, offered the following amendment to soothe the Antifederalists of his home state: VII. That each state shall have to provide for organising arming and disciplining its militia, when no provision for that purpose shall have been made by Congress and until such provision shall have been made; and that the militia shall never be subjected to martial law but in time of war rebellion or insurrection. The convention accepted some of his recommendations, but the New York proposed amendments on the subject began with: "That the People have a right to keep and bear Arms; that a well regulated Militia, including the body of the People capable of bearing Arms, is the proper, natural and safe defence of a free State;" North Carolina, which refused to ratify any Constitution until a Bill of Rights was adopted, proclaimed in their Declaration of Rights a repetition of Virginia's article 17. When presented to Congress in 1789, James Madison's original resolution, a compilation of the suggestions from the state conventions, read: The right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed; a well armed, and well regulated militia being the best security of a free country: but no person religiously scrupulous of bearing arms, shall be compelled to render military service in person. 4 Upon arrival in the Senate, it had been altered to read: ARTICLE THE FIFTH A well regulated militia, composed of the body of the People, being the best security of a free State, the right of the People to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed, but no one religiously scrupulous of bearing arms, shall be compelled to render military service in person. On September 4, 1791, the Senate disagreed by a vote of 9 - 6 to a motion to add the following: that standing armies, in time of peace, being dangerous to Liberty, should be avoided as far as the circumstances and protection of the community will admit; and that in all cases the military should be under strict subordination to, and governed by the civil Power. That no standing army or regular troops shall be raised in time of peace, without the consent of two thirds of the Members present in both Houses, and that no soldier shall be inlisted for any longer of term than the continuance of the war. On the same day, the Senate agreed to amend Article 5 to read: A well regulated militia, being the best security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed. On September 9, it was changed again to: A well regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed. Also on September 9, the Senate refused to insert "for the common defence" after "to keep and bear arms," and the article was renumbered to its familiar number 2. So much for Justice McReynolds' "common defense" excuse. The defeat of this motion distinctly places any "collective" interpretation into the realm of smoke and mirrors where it so rightfully belongs. * * *

https://www.scribd.com/document/379702733/United-States-v-Miller-307-US-174-1939

https://www.scribd.com/document/442305811/Aymette-v-The-State-21-Tenn-154-1840-RKBA

https://www.scribd.com/document/442305933/Sonzinsky-v-United-States-300-US-506-1937-RKBA

Aymette was a state case involving concealed carry. Not relevant to Miller.

In the absence of any evidence tending to show that possession or use of a "shotgun having a barrel of less than eighteen inches in length" at this time has some reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia, we cannot say that the Second Amendment guarantees the right to keep and bear such an instrument. Certainly it is not within judicial notice that this weapon is any part of the ordinary military equipment, or that its use could contribute to the common defense. Again, it demonstrates the reasoning of the Miller court -- only militia-type weapons are protected.

What?? The court never said, nor implied, that. You're just making shit up. The ONLY 2A criteria set by the court was whether or not the weapon was suitable for use by a militia OR could contribute to the common defense. "With obvious purpose to assure the continuation and render possible the effectiveness of such (militia) forces, the declaration and guarantee of the Second Amendment were made. It must be interpreted and applied with that end in view."

If the Senate wished to place any "collective" interpretation into the realm of smoke and mirrors, they would have simply written "The right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed". Right? No mention of a well- regulated militia, no mention of a collective necessity to secure a free state. But they didn't because that was never the purpose of the second amendment.

This conclusion is debatable, as thirty thousand short-barrel shotguns were purchased by the U.S. government for the armed forces in World War I. Apples and oranges. Mr. Miller possessed a sawed-off, double-barreled Steven's shotgun. The Winchester Model 1897 trench gun used by the military had a 20" barrel with heat shield, held six rounds, and had a bayonet lug and sling swivels.

Why don't you try reading Miller instead of just blowing it out your ass? Aymette is the case cited as authority by Miller at 307 U.S. 178. As you like sylabi so much, look at the syllabus description of the holding in Aymette which ws cited as the authority for the above paragraph from Miller: 1. The act of 1837–8, ch. 137, sec. 2, which prohibits any person from wearing any bowie knife, or Arkansas tooth-pick, or other knife or weapon in form, shape or size resembling a bowie knife or Arkansas tooth-pick under his clothes, or con cealed about his person, does not conflict with the 26th section of the first article of the bill of rights, securing to the free white citizens the right to keep and bear arms for their common defence. 2. The arms, the right to keep and bear which is secured by the constitution, are such as are usually employed in civilized warfare, and constitute the ordinary military equipment; the legislature have the power to prohibit the keeping or wearing weapons dangerous to the peace and safety of the citizens, and which are not usual in civilized warfare. 3. The right to keep and bear arms for the common defence, is a great political right. It respects the citizens on the one hand, and the rulers on the other; and although this right must be inviolably preserved, it does not follow that the legislature is prohibited ffrom passing laws regulating the manner in which these arms may be employed. THAT is the authority for Miller, as claimed by Miller.

What the hell do you think they remanded the case to the District Court for? THE INDICTMENT, DEMURRER, MEMO OPINION, AND ASSIGNMENT OF ERRORS ON APPEAL INDICTMENT, SEPTEMBER 21, 1938 District Court United States, Western Dist. of Arkansas THE UNITED STATES INDICTMENT. 1 ct. Sec. 1132j, T 26, USC A TRUE BILL. {signed} Richard R. Hampton (?), Foreman. Filed Sept. 21, A.D. 1938 Wm. S. Wellshear, Clerk. By Truss Russell, Deputy. {no signature} U.S. Attorney In the District Court of the United States, in and for the Western District aforesaid, at the June Term thereof, A.D. 1938. The Grand Jurors of the United States, impaneled, sworn, and charged at the Term aforesaid, of the Court aforesaid, on their oath present, that Jack Miller and Frank Layton on the 18th day of April, in the year of our Lord nineteen hundred thirty-eight, in the Ft. Smith division of said district and within the jurisdiction of said Court, did unlawfully, knowingly, wilfully, and feloniously transport in interstate commerce from the town of Claremore in the State of Oklahoma to the town of Siloam Springs in the State of Arkansas a certain firearm, to-wit, a double barrel 12-guage Stevens Shotgun having a barrel less than 18 inches in length, bearing identification number 76230, said defendants, at the time of so transporting said firearm in interstate commerce as aforesaid, not having registered said firearms as required by Section 1132d of Title 26, United States Code (Act of June 26, 1934, c. 737, Sec. 4, 48 Stat. 1237), and not having in their possession a stamped-affixed written order for said firearm as provided by Section 1132c, Title 26, United States Code (June 26, 1934, c. 737, Sec. 4, 48 Stat. 1237) and the regulations issued under authority of the said Act of Congress known as the "National Firearms Act" approved June 26, 1934, contrary to the form of the statute in such case made and provided, and against the peace and dignity of the United States. Clinton R. Barry, United States Attorney. By: {signed} Duke Frederick = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = DEMURRER TO INDICTMENT, JANUARY 3, 1939 IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES THE UNITED STATES, PLAINTIFF, DEMURRER TO INDICTMENT Comes the defendants, Jack Miller and Frank Layton, and demur to the indictment, and for grounds thereof state: 1. That the indictment fails to state sufficient facts to constitute a crime under the laws and statutes of the United States. 2. That the alleged criminal act contained in the indictment as a violation of Title 26, Section 1132, United States Code, an Act of Congress known as the National Firearms Act, approved June 26th, 1934, and the provisions thereof, is not a revenue measure and is an attempt to usurp the police powers of the State and reserved to each of the States in the United States, is unconstitutional and therefore does not state facts sufficient to constitute a crime under the statutes of the United States. 3. That the Second Amendment to the Constitution of the United States provides: "A well regulated militia being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed;" that the said "National Firearms Act" is in violation and contrary to said Second Amendment and particularly as charging a crime against these defendants under the allegations of the indictment, is unconstitutional and therefore does not state facts sufficient to constitute a crime under the statutes of the United States. 4. That the indictment herein charges the violation of Section 1132 (c) in which it is made unlawful to transfer a firearm which has previously been transferred on or after the 30th day of June, 1934, in addition to complying with subsection (c) , transfers therewith the stamp affixed order; that there is no charge in the said indictment that the said defendants made any transfer whatsoever of the double-barrel 12 guage shotgun having less than 18 inches in length, and said indictment, therefore, does not charge facts sufficient to constitute a crime under the laws and statutes of the United States. 5. That the indictment charges the defendants with "not having in their possession a stamp affixed written order for said firearms, as provided and required by Section 1132 (c), Title 26, United States Code, and the regulations issued under the authority of said Act of Congress known as the National Firearms Act, approved June 26th, 1934"; that said Section 1132 (c) does not make it a violation to merely fail to possess a stamp affixed written order for said firearms, and a failure to charge a transfer by or to the said defendants, fails to set forth facts sufficient to constitute a crime under the laws and statutes of the United States. 6. That any provision of the said National Firearms Act, approved June 26th, 1934, which requires a registration of the said firearm as required by Section 1132 (d) of Title 26 United States Code, and not having in their possession a stamp affixed order for said firearm as provided by Section 1132 (c) Title 26 United States Code, is in violation and contrary to the said Second Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, is unconstitutional and does not state facts sufficient to constitute a crime under the statutes of the United States and the indictment further does not state sufficient facts to constitute a crime under the laws and statutes of the United States in that there was a total failure to charge a transfer of said firearms by or to the said defendants. {signed} Paul E. Gutensohn = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = MEMO OPINION, JANUARY 3, 1939 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT United States, Plaintiff, MEMO. OPINION The defendants in this case are charged with unlawfully and feloniously transporting in interstate commerce from the town of Claremore, Oklahoma, to the town of Siloam Springs in the State of Arkansas, a double barrel twelve gauge shot gun having a barrel less than eighteen inches in length, and at the time of so transporting said fire arm in interstate commerce they did not have in their possession a stamp-affixed written order for said fire arm as required by Section 1132 c, Title 26 U. S. C. A., and the regulations issued under the authority of said Act of Congress known as the National Fire Arms Act. The defendants in due time filed a demurrer challenging the sufficiency of the facts stated in the indictment to constitute a crime and further challenging the sections under which said indictment was returned as being in contravention of the Second Amendment to the Constitution of the United States. The indictment is based upon the Act of June 26, 1934, C.757, Section 11, 48 Statute 1239. The court is of the opinion that this section is invalid in that it violates the Second Amendment to the Constitution of the United States providing, "A well regulated militia being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed." The demurrer is accordingly sustained. This the 3rd day of January 1939. {signed} Heartsill Ragon = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = ASSIGNMENTS OF ERROR IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff, ASSIGNMENTS OF ERROR Comes now the United States of America by Clinton R. Barry, United States Attorney for the Western District of Arkansas, and avers that in the record proceedings and judgment herein there is manifest error and against the just rights of the said plaintiff, in this, to wit: 1. That the court committed material error against the plaintiff in holding that Section 11 of the National Firearms Act of June 26, 1934, c. 757, 48 Stat. 1236, 1239, is invalid as violating the Second Amendment to the Constitution of the United States providing that "A well regulated militia being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed." 2. That the court committed material error against the plaintiff in sustaining the demurrer of the defendants Jack Miller and Frank Layton to the indictment. {signed} Clinton R. Barry CLINTON R. BARRY

This conclusion is debatable, as thirty thousand short-barrel shotguns were purchased by the U.S. government for the armed forces in World War I. The Opinion of the Court at page 178 reads: In the absence of any argument or evidence, it is not debatable that the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously found it certainly could not take judicial notice that a sawed off shotgun was then, at that time, bearing some relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia. The Court did not say the sawed off shotgun did, or did not, bear some relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia. As the Court could not state that the sawed off did bear such relationship in the absence of evidence, it could not uphold the demurrer and remanded the case to the District Court for further proceedings. By then Miller was dead. To the Court's refusal to assume as fact, a point for which no argument or evidence was presented, it is irrelevant if thousands of such weapons were actually being used by the military.

https://cdn.loc.gov/service/ll/usrep/usrep521/usrep521898/usrep521898.pdf Printz v. United States, 521 U.S. 898, 938 n.1 (1997)(Thomas, J., concurring)

https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/appellate-courts/F2/131/916/1511728/ Cases v. United States, 131 F.2d 916 (1st Cir. 1942) The right to keep and bear arms is not a right conferred upon the people by the federal constitution. Whatever rights in this respect the people may have depend upon local legislation; the only function of the Second Amendment being to prevent the federal government and the federal government only from infringing that right. *922 United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 542, 553, 23 L. Ed. 588; Presser v. Illinois, 116 U.S. 252, 265, 6 S. Ct. 580, 29 L. Ed. 615. But the Supreme Court in a dictum in Robertson v. Baldwin, 165 U.S. 275, 282, 17 S. Ct. 326, 41 L. Ed. 715, indicated that the limitation imposed upon the federal government by the Second Amendment was not absolute and this dictum received the sanction of the court in the recent case of United States v. Miller, 307 U.S. 174, 182, 59 S. Ct. 816, 83 L. Ed. 1206. In the case last cited the Supreme Court, after discussing the history of militia organizations in the United States, upheld the validity under the Second Amendment of the National Firearms Act of June 26, 1934, 48 Stat. 1236, in so far as it imposed limitations upon the use of a shotgun having a barrel less than eighteen inches long. It stated the reason for its result on page 178 of the opinion in 307 U.S., on page 818 of 59 S.Ct., 83 L. Ed. 1206, as follows: "In the absence of any evidence tending to show that possession or use of a 'shotgun having a barrel of less than eighteen inches in length' at this time has some reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia, we cannot say that the Second Amendment guarantees the right to keep and bear such an instrument. Certainly it is not within judicial notice that this weapon is any part of the ordinary military equipment or that its use could contribute to the common defense." Apparently, then, under the Second Amendment, the federal government can limit the keeping and bearing of arms by a single individual as well as by a group of individuals, but it cannot prohibit the possession or use of any weapon which has any reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia. However, we do not feel that the Supreme Court in this case was attempting to formulate a general rule applicable to all cases. The rule which it laid down was adequate to dispose of the case before it and that we think was as far as the Supreme Court intended to go. At any rate the rule of the Miller case, if intended to be comprehensive and complete would seem to be already outdated, in spite of the fact that it was formulated only three and a half years ago, because of the well known fact that in the so called "Commando Units" some sort of military use seems to have been found for almost any modern lethal weapon. In view of this, if the rule of the Miller case is general and complete, the result would follow that, under present day conditions, the federal government would be empowered only to regulate the possession or use of weapons such as a flintlock musket or a matchlock harquebus. But to hold that the Second Amendment limits the federal government to regulations concerning only weapons which can be classed as antiques or curiosities, almost any other might bear some reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia unit of the present day, is in effect to hold that the limitation of the Second Amendment is absolute. Another objection to the rule of the Miller case as a full and general statement is that according to it Congress would be prevented by the Second Amendment from regulating the possession or use by private persons not present or prospective members of any military unit, of distinctly military arms, such as machine guns, trench mortars, anti-tank or anti-aircraft guns, even though under the circumstances surrounding such possession or use it would be inconceivable that a private person could have any legitimate reason for having such a weapon. It seems to us unlikely that the framers of the Amendment intended any such result. Considering the many variable factors bearing upon the question it seems to us impossible to formulate any general test by which to determine the limits imposed by the Second Amendment but that each case under it, like cases under the due process clause, must be decided on its own facts and the line between what is and what is not a valid federal restriction pricked out by decided cases falling on one side or the other of the line. We therefore turn to the record in the case at bar. From it it appears that on or about August 27, 1941, the appellant received into his possession and carried away ten rounds of ammunition, and that on the evening of August 30 of the same year he went to Annadale's Beach Club on Isla Verde in the municipality of Carolina, Puerto Rico, equipped with a .38 caliber Colt type revolver of Spanish make which, when some one turned out the lights, he used, apparently not wholly without effect, upon another patron of the place who in some way seems to have incurred his displeasure. While the weapon may be capable of military use, or while at least *923 familiarity with it might be regarded as of value in training a person to use a comparable weapon of military type and caliber, still there is no evidence that the appellant was or ever had been a member of any military organization or that his use of the weapon under the circumstances disclosed was in preparation for a military career. In fact, the only inference possible is that the appellant at the time charged in the indictment was in possession of, transporting,[3] and using the firearm and ammunition purely and simply on a frolic of his own and without any thought or intention of contributing to the efficiency of the well regulated militia which the Second Amendment was designed to foster as necessary to the security of a free state. We are of the view that, as applied to the appellant, the Federal Firearms Act does not conflict with the Second Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

Again, it demonstrates the reasoning of the Miller court -- only militia-type weapons are protected. https://www.lclark.edu/live/files/771 Nelson Lund, Heller and Second Amendment Precedent, 13 Lewis & Clark L. Rev. 335, 336-39 (2009) [excerpt at 337-39, footnotes omitted] A duly interposed demurrer alleged: The National Firearms Act is not a revenue measure but an attempt to usurp police power reserved to the States, and is therefore unconstitutional. Also, it offends the inhibition of the Second Amendment to the Constitution—“A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” The District Court held that section eleven of the Act violates the Second Amendment. It accordingly sustained the demurrer and quashed the indictment. The cause is here by direct appeal. Besides the fact that the Supreme Court was reviewing a bare and unexplained judgment sustaining a demurrer, the criminal defendants failed to appear in the Supreme Court—as the Court was careful to report. Thus, neither the court below nor the criminal defendants offered the Supreme Court any argument in support of the challenged judgment, and the Justices heard arguments only from the government. After such a stunted adversarial process, and with no Supreme Court precedents to guide the Court’s interpretation, one would expect a narrow and even tentative decision. That is just what the Court delivered. After quickly disposing of the federalism issue (which the trial court had not addressed), the Miller Court stated its conclusion about the Second Amendment as follows: This passage states the holding in the case. Note that the Court does not hold that short-barreled shotguns are outside the coverage of the Second Amendment. The Court says only that it has seen no evidence that these weapons have certain militia-related characteristics—which is no surprise given the procedural posture of the case—and that the Court could not take judicial notice of certain facts about the military utility of these weapons. After this statement, one would expect the case to be remanded to give the defendants an opportunity to offer the kind of evidence called for in the Court’s holding. Sure enough, Miller concludes as follows: “We are unable to accept the conclusion of the court below and the challenged judgment must be reversed. The cause will be remanded for further proceedings.” The legal test that the trial court would have been required to employ on remand is that there is a right to keep and bear a particular weapon only if, at a minimum, the weapon “has some reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia” which could be shown, for example, by evidence that the weapon is “part of the ordinary military equipment or that its use could contribute to the common defense.” Given the procedural posture of the case, the Supreme Court’s language could not possibly be read to mean that short-barreled shotguns are outside the protection of the Second Amendment, or that the provisions of the National Firearms Act regulating these weapons had been found to be constitutionally valid. The implications of Miller would be very different if the Court had upheld a conviction for violating the statute rather than what it in fact did, namely to reverse the trial court’s unexplained decision to sustain a demurrer. If a conviction had been upheld, it would have meant that there is no Second Amendment bar to the statutory requirements that the defendants were charged with violating. Depending on how the Court had explained such a conclusion, it might also have meant that short-barreled shotguns are unprotected by Second Amendment protection. In fact, however, there is no basis for either of these conclusions in the Miller opinion.

To determine whether or not a sawed-off shotgun was suitable for use by a militia.

Sure. But they weren't. Mr. Miller's Stevens 311 sawed-off shotgun: WWI military trench gun -- Wichester M97

Please quote the opinion where it says only militia-type weapons are protected. Please quote the opinion where it says all militia-type weapons are protected. - - - - - - - - - - Clayton E. Cramer, For the Defense of Themselves and the State, The Original Intent and Judicial Interpretation of the Right to Keep and Bear Arms, Praeger Publishers, 1994, page 189: The Court did not say that a short-barreled shotgun was unprotected—just that no evidence had been presented to demonstrate such a weapon was "any part of the ordinary military equipment" or that it could "contribute to the common defense." - - - - - - - - - - Brian L. Frye, The Peculiar Story of United States v. Miller, NYU Journal of Law and Liberty, Vol 3:48 at 50: - - - - - - - - - - https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=960812 Brannon P. Denning and Glenn H. Reynolds, Telling Miller's Tale: A Reply to David Yassky, 65 Law & Contemp. Probs. 113, 118 (Spring 2002). It is true that "[t]he Court [in Miller] did not ... attempt to define, or otherwise construe, the substantive right protected by the Second Amendment."

That's NOT what the Miller court said. It limited it's ruling to the TYPE of weapon protected by the second amendment. It NEVER said who may possess such a weapon or who may use such a weapon.