U.S. Constitution

See other U.S. Constitution Articles

Title: Welcome to the Quiet Skies (TSA)

Source:

Boston Globe

URL Source: https://apps.bostonglobe.com/news/n ... phics/2018/07/tsa-quiet-skies/

Published: Jul 29, 2018

Author: Jana Winter

Post Date: 2018-07-29 21:09:58 by Hondo68

Keywords: You look suspicious, TSA secret missions, domestic surveillance program

Views: 1451

Comments: 4

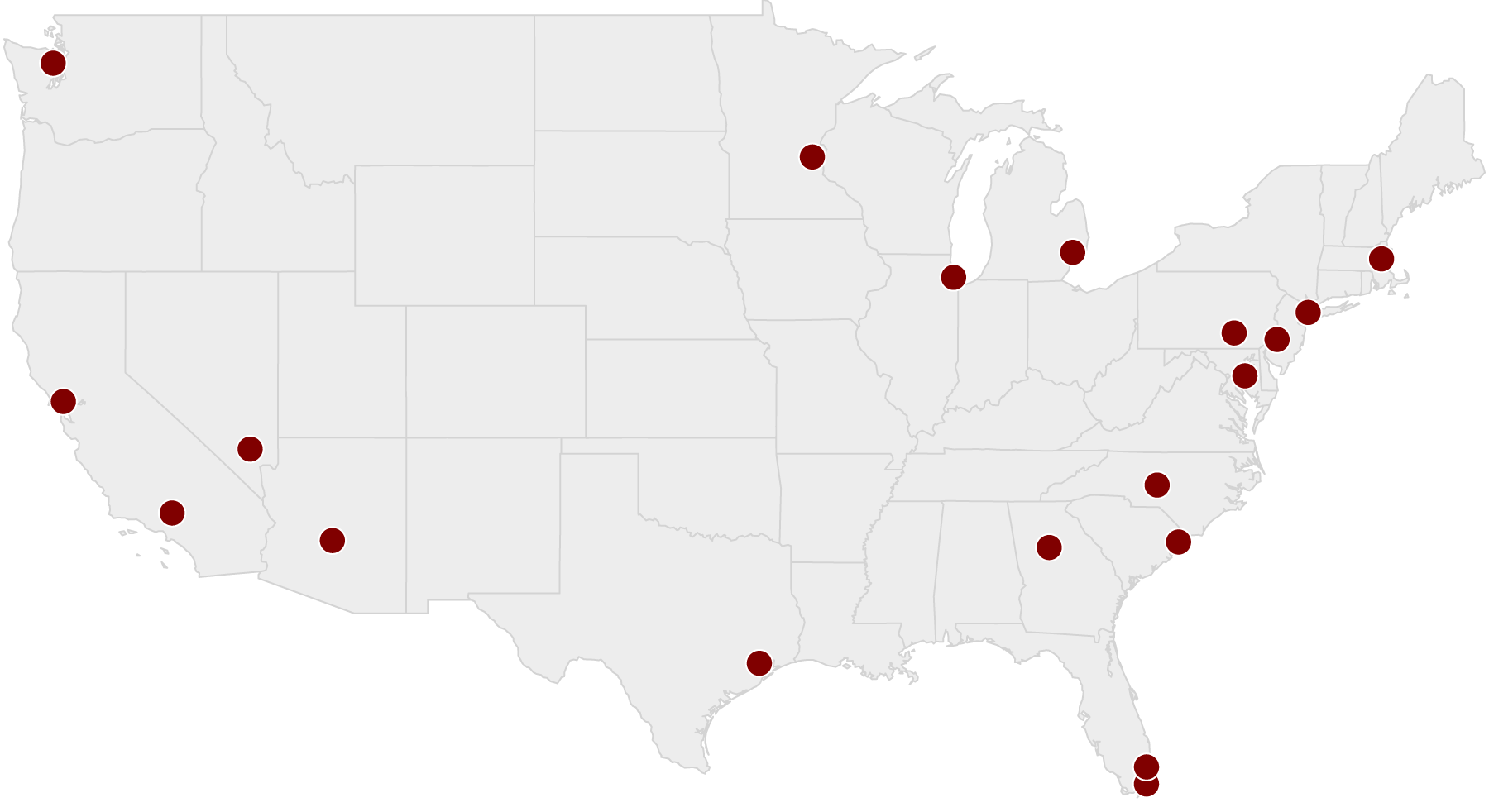

Did you scan the boarding area from afar? Have a cold, penetrating stare? Sleep on the plane? Use the bathroom? Talk to others? Federal air marshals have begun following ordinary US citizens not suspected of a crime or on any terrorist watch list and collecting extensive information about their movements and behavior under a new domestic surveillance program that is drawing criticism from within the agency. The previously undisclosed program, called “Quiet Skies,” specifically targets travelers who “are not under investigation by any agency and are not in the Terrorist Screening Data Base,” according to a Transportation Security Administration bulletin in March. The internal bulletin describes the program’s goal as thwarting threats to commercial aircraft “posed by unknown or partially known terrorists,” and gives the agency broad discretion over which air travelers to focus on and how closely they are tracked. But some air marshals, in interviews and internal communications shared with the Globe, say the program has them tasked with shadowing travelers who appear to pose no real threat — a businesswoman who happened to have traveled through a Mideast hot spot, in one case; a Southwest Airlines flight attendant, in another; a fellow federal law enforcement officer, in a third. It is a time-consuming and costly assignment, they say, which saps their ability to do more vital law enforcement work. TSA officials, in a written statement to the Globe, broadly defended the agency’s efforts to deter potential acts of terror. But the agency declined to discuss whether Quiet Skies has intercepted any threats, or even to confirm that the program exists. Release of such information “would make passengers less safe,” spokesman James Gregory said in the statement. Already under Quiet Skies, thousands of unsuspecting Americans have been subjected to targeted airport and inflight surveillance, carried out by small teams of armed, undercover air marshals, government documents show. The teams document whether passengers fidget, use a computer, have a “jump” in their Adam’s apple or a “cold penetrating stare,” among other behaviors, according to the records. Air marshals note these observations — minute-by-minute — in two separate reports and send this information back to the TSA. All US citizens who enter the country are automatically screened for inclusion in Quiet Skies — their travel patterns and affiliations are checked and their names run against a terrorist watch list and other databases, according to agency documents. (If observed, check any that apply below) | Y N Unknown (If observed, check any that apply below) | Y N Unknown (If yes, check any that apply below) | Y N Unknown (If observed, check any that apply below) | Y N Unknown (Provide detailed descriptions of any electronic devices in subject’s possession in AAR) | Y N Unknown (If possible, provide identifiers (license plate, vehicle description) of pick up vehicle in AAR) | Y N Unknown The program relies on 15 rules to screen passengers, according to a May agency bulletin, and the criteria appear broad: “rules may target” people whose travel patterns or behaviors match those of known or suspected terrorists, or people “possibly affiliated” with someone on a watch list. The full list of criteria for Quiet Skies screening was unavailable to the Globe, and is a mystery even to the air marshals who field the surveillance requests the program generates. TSA declined to comment. When someone on the Quiet Skies list is selected for surveillance, a team of air marshals is placed on the person’s next flight. The team receives a file containing a photo and basic information — such as date and place of birth — about the target, according to agency documents. The teams track citizens on domestic flights, to or from dozens of cities big and small — such as Boston and Harrisburg, Pa., Washington, D.C., and Myrtle Beach, S.C. — taking notes on whether travelers use a phone, go to the bathroom, chat with others, or change clothes, according to documents and people within the department. Air marshals are following citizens to or from cities big and small, including these airports Quiet Skies represents a major departure for TSA. Since the Sept. 11 attacks, the agency has traditionally placed armed air marshals on routes it considered potentially higher risk, or on flights with a passenger on a terrorist watch list. Deploying air marshals to gather intelligence on civilians not on a terrorist watch list is a new assignment, one that some air marshals say goes beyond the mandate of the US Federal Air Marshal Service. Some also worry that such domestic surveillance might be illegal. Between 2,000 and 3,000 men and women, so-called flying FAMs, work the skies. Since this initiative launched in March, dozens of air marshals have raised concerns about the Quiet Skies program with senior officials and colleagues, sought legal counsel, and expressed misgivings about the surveillance program, according to interviews and documents reviewed by the Globe. “What we are doing [in Quiet Skies] is troubling and raising some serious questions as to the validity and legality of what we are doing and how we are doing it,” one air marshal wrote in a text message to colleagues. The TSA, while declining to discuss details of the Quiet Skies program, did address generally how the agency pursues its work. “FAMs [federal air marshals] may deploy on flights in furtherance of the TSA mission to ensure the safety and security of passengers, crewmembers, and aircraft throughout the aviation sector,” spokesman James Gregory said in an e-mailed statement. “As its assessment capabilities continue to enhance, FAMS leverages multiple internal and external intelligence sources in its deployment strategy.” Agency documents show there are about 40 to 50 Quiet Skies passengers on domestic flights each day. On average, air marshals follow and surveil about 35 of them. In late May, an air marshal complained to colleagues about having just surveilled a working Southwest Airlines flight attendant as part of a Quiet Skies mission. “Cannot make this up,” the air marshal wrote in a message. One colleague replied: “jeez we need to have an easy way to document this nonsense. Congress needs to know that it’s gone from bad to worse.” Experts on civil liberties called the Quiet Skies program worrisome and potentially illegal. “These revelations raise profound concerns about whether TSA is conducting pervasive surveillance of travelers without any suspicion of actual wrongdoing,” said Hugh Handeyside, senior staff attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union’s National Security Project. “If TSA is using proxies for race or religion to single out travelers for surveillance, that could violate the travelers’ constitutional rights. These concerns are all the more acute because of TSA’s track record of using unreliable and unscientific techniques to screen and monitor travelers who have done nothing wrong.” George Washington University law professor Jonathan Turley said Quiet Skies touches on several sensitive legal issues and appears to fall into a gray area of privacy law. If this was about foreign citizens, the government would have considerable power. But if it’s US citizens — US citizens don’t lose their rights simply because they are in an airplane at 30,000 feet. — Jonathan Turley, George Washington University law professor “If this was about foreign citizens, the government would have considerable power. But if it’s US citizens — US citizens don’t lose their rights simply because they are in an airplane at 30,000 feet,” Turley said. “There may be indeed constitutional issues here depending on how restrictive or intrusive these measures are.” Turley, who has testified before Congress on privacy protection, said the issue could trigger a “transformative legal fight.” Geoffrey Stone, a University of Chicago law professor chosen by President Obama in 2013 to help review foreign intelligence surveillance programs, said the program could pass legal muster if the selection criteria are sufficiently broad. But if the program targets by nationality or race, it could violate equal protection rights, Stone said. Asked about the legal basis for the Quiet Skies program, Gregory, the agency’s spokesman, said TSA “maintains a robust engagement with congressional committees to ensure maximum support and awareness” of its effort to keep the aviation sector safe. He declined to comment further. Beyond the legalities, some air marshals believe Quiet Skies is not a sound use of limited agency resources. Several air marshals, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because they are not authorized to speak publicly, told the Globe the program wastes taxpayer dollars and makes the country less safe because attention and resources are diverted away from legitimate, potential threats. The US Federal Air Marshal Service, which is part of TSA and falls under the Department of Homeland Security, has a mandate to protect airline passengers and crew against the risk of criminal and terrorist violence. John Casaretti, president of the Air Marshal Association, said in a statement: “The Air Marshal Association believes that missions based on recognized intelligence, or in support of ongoing federal investigations, is the proper criteria for flight scheduling. Currently the Quiet Skies program does not meet the criteria we find acceptable. “The American public would be better served if these [air marshals] were instead assigned to airport screening and check in areas so that active shooter events can be swiftly ended, and violations of federal crimes can be properly and consistently addressed.” TSA has come under increased scrutiny from Congress since a 2017 Government Accountability Office report raised questions about its management of the Federal Air Marshal Service. Requested by Congress, the report noted that the agency, which spent $800 million in 2015, has “no information” on its effectiveness in deterring attacks. Late last year, Representative Jody Hice, a Georgia Republican, introduced a bill that would require the Federal Air Marshal Service to better incorporate risk assessment in its deployment strategy, provide detailed metrics on flight assignments, and report data back to Congress. Without this information, Congress, TSA, and the Department of Homeland Security “are not able to effectively conduct oversight” of the air marshals, Hice wrote in a letter to colleagues. “With threats coming at us left and right, our focus should be on implementing effective, evidence-based means of deterring, detecting, and disrupting plots hatched by our enemies.” Hice’s bill, the “Strengthening Aviation Security Act of 2017,” passed the House and is awaiting consideration by the full Senate. The Globe, in its review of Quiet Skies, examined numerous TSA internal bulletins, directives, and internal communications, and interviewed more than a dozen people with direct knowledge of the program. The purpose of Quiet Skies is to decrease threats by “unknown or partially known terrorists; and to identify and provide enhanced screening to higher risk travelers before they board aircraft based on analysis of terrorist travel trends, tradecraft and associations,” according to a TSA internal bulletin. The criteria for surveillance appear fluid. Internal agency e-mails show some confusion about the program’s parameters and implementation. A bulletin in May notes that travelers entering the United States may be added to the Quiet Skies watch list if their “international travel patters [sic] or behaviors match the travel routing and tradecraft of known or suspected terrorists” or “are possibly affiliated with Watch Listed suspects.” Travelers remain on the Quiet Skies watch list “for up to 90 days or three encounters, whichever comes first, after entering the United States,” agency documents show. Travelers are not notified when they are placed on the watch list or have their activity and behavior monitored. Quiet Skies surveillance is an expansion of a long-running practice in which federal air marshals are assigned to surveil the subject of an open FBI terrorism investigation. In such assignments, air marshal reports are relayed back to the FBI or another outside law enforcement agency. In Quiet Skies, these same reports are completed in the same manner but stay within TSA, agency documents show, and details are shared with outside agencies only if air marshals observe “significant derogatory information.” According to a TSA bulletin, the program may target people who have spent a certain amount of time in one or more specific countries or whose reservation information includes e-mail addresses or phone numbers associated to suspects on a terrorism watch list. The bulletin does not list the specific countries, but air marshals have been advised in several instances to follow passengers because of past travel to Turkey, according to people with direct knowledge of the program. One air marshal described an assignment to conduct a Quiet Skies mission on a young executive from a major company. “Her crime apparently was she flew to Turkey in the past,” the air marshal said, noting that many international companies have executives travel through Turkey. “According to the government’s own [Department of Justice] standards there is no cause to be conducting these secret missions.” Poster Comment: You're all criminals, what are you planning to do?

This is just some of the information that federal air marshals collect on thousands of regular US citizens under a secret, domestic surveillance program.

Brynn Anderson/Associated Press Explore the behavior checklist

1. Subject was abnormally aware of surroundings

2. Subject exhibited Behavioral Indicators

3. Subject’s appearance was different from information provided

4. Subject slept during the flight

5. General Observations

6. For Domestic Arrivals Only

Flying the quiet skies

Post Comment Private Reply Ignore Thread

Top • Page Up • Full Thread • Page Down • Bottom/Latest

Begin Trace Mode for Comment # 1.

#1. To: hondo68 (#0)

You should have your ass probed by one of Gary Johnson's faggots every time you fly in light of your threat to kill the President.

#2. To: A K A Stone, *2020 The Likely Suspects* (#1)

Isn't you fantasy legal in Gov Kashich's State? The 2020 Libertarian Presidential ticket?

Top • Page Up • Full Thread • Page Down • Bottom/Latest

Replies to Comment # 1. ass probed by one of Gary Johnson's faggots

End Trace Mode for Comment # 1.

[Home] [Headlines] [Latest Articles] [Latest Comments] [Post] [Mail] [Sign-in] [Setup] [Help] [Register]